Understanding Network Devices: The Journey from Internet to Your Application

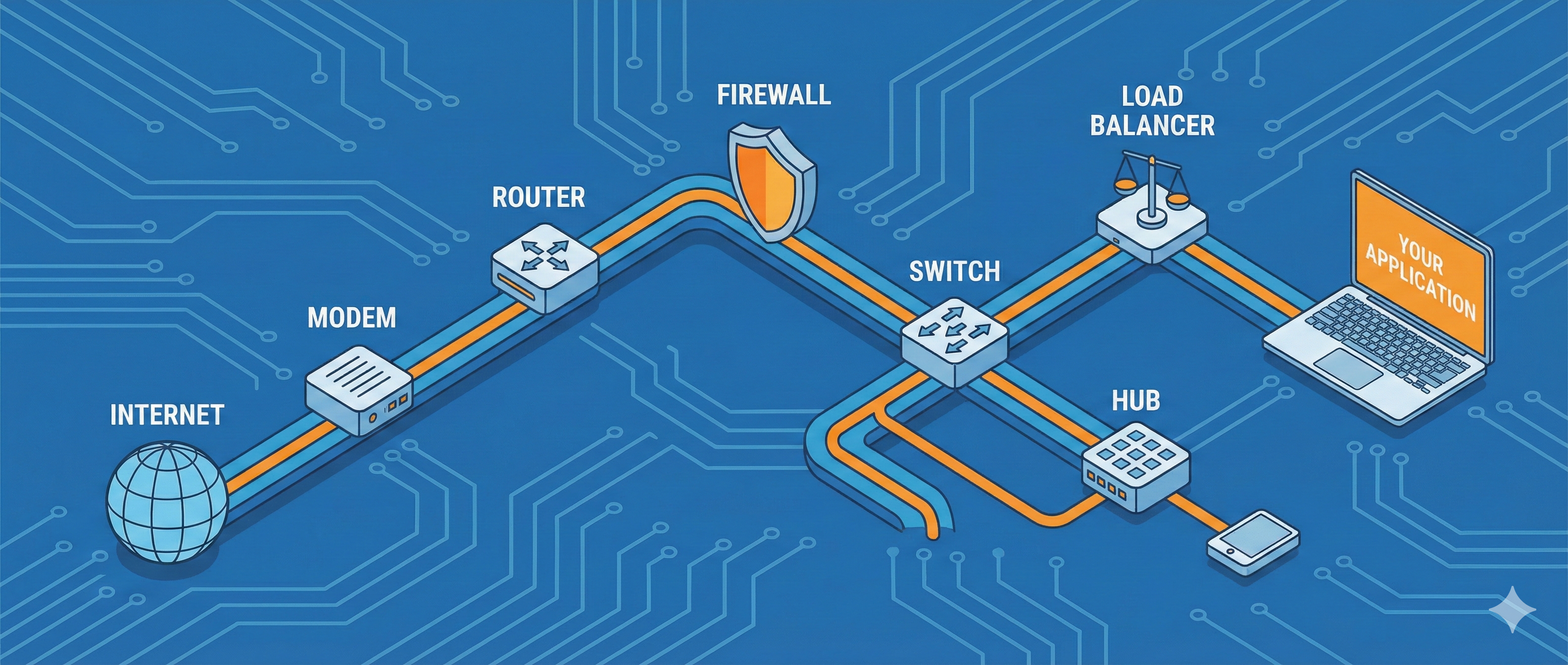

Ever wondered how data travels from the internet to your laptop, or how Netflix handles millions of requests without crashing? This deep dive explores the essential networking hardware that makes modern internet possible - modems, routers, switches, hubs, firewalls, and load balancers - and shows how they work together in real-world systems.

When you type a URL in your browser and hit enter, an incredible chain of events unfolds. Data travels through multiple devices, each with a specific job, working in perfect harmony to deliver that webpage to your screen. As developers, we often work at the application layer, writing APIs and building frontends, but understanding the hardware layer beneath can transform how you architect systems.

Today, I want to take you on a journey through the physical devices that power the internet. Not just what they do, but why they exist, how they differ from each other, and how they all fit together in a real-world network architecture.

The Big Picture: How the Internet Reaches You

Before we dive into individual devices, let's understand the journey of data from the internet to your computer:

Internet (Cloud)

↓

[Modem] ← Converts signals (analog ↔ digital)

↓

[Router] ← Directs traffic between networks

↓

[Firewall] ← Security checkpoint

↓

[Switch] ← Connects devices intelligently

↓

Your Devices (Laptop, Phone, etc.)

For a web application in production, the architecture looks more like this:

Users worldwide

↓

[Load Balancer] ← Distributes traffic

↓

Multiple Web Servers

↓

[Internal Firewall]

↓

Database Servers

Each device serves a specific purpose. Let's explore them one by one.

The Modem: Your Gateway to the Internet

What is a Modem?

The word "modem" stands for modulator-demodulator. It's the device that connects your home or office network to your Internet Service Provider (ISP), and ultimately, to the internet.

Why Do We Need Modems?

Here's the problem: your computer speaks digital (0s and 1s), but traditional telephone lines and cable networks transmit analog signals (continuous waves). The modem is the translator between these two worlds.

Analogy: Think of a modem as a language interpreter at the border. Your computer speaks "Digital" and the telephone network speaks "Analog". The modem translates between them in real-time, in both directions.

How Modems Work

The modem performs two critical operations:

Modulation (Digital → Analog): When you send data (like uploading a file), the modem converts your computer's digital signals into analog signals that can travel through telephone lines or cable networks.

Demodulation (Analog → Digital): When you receive data (like loading a webpage), the modem converts the incoming analog signals from your ISP back into digital signals your computer can understand.

The Process:

- Data Generation: Your computer generates digital data (0s and 1s)

- Modulation: Modem encodes this data onto a carrier wave (analog signal)

- Transmission: The analog signal travels through physical cables to your ISP

- Reception: Your ISP's modem receives the signal

- Demodulation: Signal is converted back to digital data

- Delivery: Data reaches its destination on the internet

Types of Modems

Cable Modem: Uses cable TV infrastructure for high-speed internet access. Common in residential setups.

DSL Modem: Works over telephone lines. Slower than cable but widely available.

Fiber Optic Modem: Converts digital signals to light pulses. Extremely fast, used in modern fiber internet connections.

Satellite Modem: Provides internet through satellite dishes. Useful in remote areas where cable infrastructure doesn't exist.

Key Characteristics:

- Connects only one network to the internet (no internal network management)

- Limited device connectivity (usually needs a router for multiple devices)

- Operates at the Physical Layer (Layer 1) and Data Link Layer (Layer 2) of the OSI model

The Router: Traffic Controller of Networks

What is a Router?

A router is a networking device that forwards data packets between different networks. While a modem connects you to the internet, a router creates and manages your local network, directing traffic between your devices and the internet.

Analogy: If the modem is the border crossing to the internet, the router is the traffic police officer directing vehicles (data packets) to their correct destinations using street addresses (IP addresses).

Why Do We Need Routers?

Imagine you have multiple devices - laptop, phone, smart TV, tablet - all wanting to access the internet through one modem. The router makes this possible by:

- Creating a Local Network: Builds a LAN (Local Area Network) for all your devices

- Managing Traffic: Ensures each device gets the data it requested

- Providing Security: Acts as a barrier between your devices and the internet

- Assigning IP Addresses: Gives each device a unique local IP address

How Routers Work

Routers operate at the Network Layer (Layer 3) of the OSI model, using IP addresses to make routing decisions.

Core Functions:

IP Address Management: Your router uses DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol) to automatically assign IP addresses to devices on your network. Each device gets a private IP address (like 192.168.1.5).

Routing Tables: Routers maintain routing tables - databases containing the best paths to forward packets to different destinations. When a packet arrives, the router:

- Inspects the destination IP address

- Consults its routing table

- Determines the best route

- Forwards the packet to the next hop

Network Address Translation (NAT): This is crucial. Your router has one public IP address (visible to the internet) but manages multiple devices with private IP addresses. NAT translates between these:

- Outgoing: Converts private IP → public IP

- Incoming: Converts public IP → correct private IP

This is how multiple devices share one internet connection.

Example Flow:

Your laptop (192.168.1.10) wants to access google.com

1. Laptop sends request to router

2. Router replaces source IP (192.168.1.10) with its public IP (203.0.113.45)

3. Google responds to 203.0.113.45

4. Router receives response, checks NAT table

5. Router forwards to 192.168.1.10 (your laptop)

Types of Routers

Wired Router: Connects devices via Ethernet cables. Reliable, fast, commonly used in offices.

Wireless Router: Includes Wi-Fi capability. Most home routers are wireless, broadcasting an SSID (Service Set Identifier) - that's your Wi-Fi network name.

Core Router: Used by ISPs and large organizations. Operates at the "core" of a network, handling massive traffic volumes. Doesn't communicate with external networks.

Edge Router: Lives at the network "edge", communicating between internal networks and external networks using protocols like BGP (Border Gateway Protocol).

Virtual Router: Software-based router running on virtual machines. Commonly used in cloud environments.

Router vs Modem: The Key Difference

Modem: Connects your network to the internet (network ↔ internet) Router: Connects devices within your network and manages traffic (device ↔ device, device ↔ internet)

Most modern "routers" you buy are actually modem-router combos that do both jobs.

Switch vs Hub: The Intelligence Gap

Now that we're inside the local network (thanks to the router), let's talk about how devices connect to each other. This is where switches and hubs come in - and trust me, the difference matters.

The Humble Hub: Broadcasting Everything

A hub is the simplest networking device. It operates at the Physical Layer (Layer 1) of the OSI model.

How a Hub Works: When a hub receives data on one port, it broadcasts that data to all other ports. Every connected device receives every packet, even if it's not meant for them.

Analogy: Imagine a meeting room where every time someone wants to talk to one person, they shout so everyone can hear. Everyone must listen to every message and figure out if it's for them.

The Problems:

-

Collision Domain: All devices share one collision domain. If two devices transmit simultaneously, a collision occurs, and both must retransmit.

-

Security Risk: Every device sees all traffic, making it easy to eavesdrop.

-

Wasted Bandwidth: Unnecessary traffic floods all ports, slowing down the network.

-

No Intelligence: Hubs don't understand MAC addresses or IP addresses - they're "dumb" repeaters.

Types of Hubs:

- Active Hub: Amplifies signals, requires power

- Passive Hub: Simply connects devices without amplification

Hubs are largely obsolete today. Switches have replaced them in almost every scenario.

The Intelligent Switch: Smart Delivery

A switch is a smart device that operates at the Data Link Layer (Layer 2) of the OSI model.

How a Switch Works:

Switches learn and remember which devices are connected to which ports using MAC addresses. They maintain a MAC address table (CAM table) that maps MAC addresses to physical ports.

The Learning Process:

Initial State: MAC table is empty

Device A (MAC: AA:AA:AA:AA:AA:AA) sends to Device B

↓

Switch receives frame on Port 1

↓

Switch learns: "Device A is on Port 1" (records in MAC table)

↓

Switch doesn't know where Device B is yet

↓

Switch broadcasts frame to all ports (except Port 1)

↓

Device B (MAC: BB:BB:BB:BB:BB:BB) responds from Port 3

↓

Switch learns: "Device B is on Port 3"

↓

Now switch knows both locations

↓

Future traffic between A and B goes directly through Ports 1 and 3

Analogy: Think of a switch as a smart postal service. Instead of delivering every letter to every house (like a hub), it knows which house each person lives in and delivers mail directly to the correct address.

Key Advantages:

-

Multiple Collision Domains: Each port is its own collision domain. Devices can transmit simultaneously without collisions.

-

Efficient Bandwidth Usage: Data only goes where it needs to go.

-

Better Security: Devices only see traffic intended for them.

-

Faster Performance: Dedicated connections reduce congestion.

Hub vs Switch: Side-by-Side Comparison

| Feature | Hub | Switch |

|---|---|---|

| OSI Layer | Layer 1 (Physical) | Layer 2 (Data Link) |

| Intelligence | None (broadcasts everything) | Learns MAC addresses |

| Collision Domains | One shared domain | Separate domain per port |

| Performance | Poor (lots of collisions) | Excellent (targeted delivery) |

| Security | Low (all traffic visible to all) | Better (isolated traffic) |

| Bandwidth | Shared across all devices | Dedicated per port |

| Use Case | Obsolete | Modern LANs |

For Software Engineers: When you deploy multiple servers in a data center, they're connected via high-speed switches, not hubs. This ensures your microservices can communicate efficiently without packet collisions.

The Firewall: Security at the Gate

You've got internet access (modem), intelligent routing (router), and smart device connectivity (switch). But now you need protection. Enter the firewall.

What is a Firewall?

A firewall is a security system that monitors and controls incoming and outgoing network traffic based on predetermined security rules. It acts as a barrier between your trusted internal network and untrusted external networks (like the internet).

Analogy: A firewall is like a security checkpoint at a building entrance. It checks everyone coming in and going out, allowing authorized people through while blocking suspicious individuals.

Why Do We Need Firewalls?

Without a firewall, your network is like a house with all doors and windows wide open. Anyone can:

- Access your computers and servers

- Steal sensitive data

- Install malware or ransomware

- Launch attacks on other systems using your resources

- Monitor your network traffic

A firewall prevents these threats by enforcing access control policies.

How Firewalls Work

Firewalls inspect network packets and make decisions based on rules:

Inspection Points:

- Source IP Address: Where is the traffic coming from?

- Destination IP Address: Where is it going?

- Port Numbers: Which service is being accessed? (Port 80 = HTTP, Port 443 = HTTPS)

- Protocol: TCP, UDP, ICMP, etc.

- Packet Content: What data is being transmitted? (Deep packet inspection)

Decision Making:

Incoming packet arrives

↓

Firewall examines packet headers

↓

Checks against rule set:

- Is source IP on blocklist?

- Is destination port allowed?

- Does content match threat signatures?

↓

Decision: ALLOW or BLOCK

↓

If ALLOWED: Forward to destination

If BLOCKED: Drop packet and log attempt

Types of Firewalls

Packet Filtering Firewall:

- Operates at Layer 3 (Network) and Layer 4 (Transport)

- Examines packet headers (IP addresses, ports, protocols)

- Fast but basic - doesn't inspect packet contents

- Example rule: "Block all traffic from IP 192.168.1.100"

Stateful Inspection Firewall:

- Tracks the state of network connections

- Remembers context of previous packets in a connection

- More secure than simple packet filtering

- Example: Allows response packets only if a request was sent first

Proxy Firewall:

- Acts as an intermediary between clients and servers

- Operates at Layer 7 (Application)

- Inspects packet contents, not just headers

- Provides additional services like caching

- Slower but more secure

Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW):

- Combines traditional firewall features with advanced capabilities

- Deep packet inspection

- Intrusion prevention system (IPS)

- Application awareness and control

- Malware defense

- URL filtering

Web Application Firewall (WAF):

- Specifically protects web applications

- Filters HTTP/HTTPS traffic

- Defends against attacks like SQL injection, XSS, CSRF

- Essential for production web apps

Firewall Placement

Perimeter Firewall: Positioned at the network edge (between router and internet)

Internet → Firewall → Router → Internal Network

Internal Firewall: Segments internal networks

Web Servers → Firewall → Database Servers

Host-Based Firewall: Software firewall on individual devices (Windows Firewall, iptables)

What Firewalls DON'T Protect Against

It's important to understand limitations:

-

Malware via Email/Downloads: If a user clicks a malicious link or downloads infected files, the malware can bypass the firewall.

-

Insider Threats: Authorized users with malicious intent already have internal access.

-

Physical Theft: Firewalls can't prevent someone from stealing hardware.

-

Social Engineering: Tricking users into revealing passwords bypasses network security.

-

Zero-Day Exploits: Unknown vulnerabilities not yet in threat databases.

Defense in Depth: Firewalls are one layer. You also need antivirus, encryption, access controls, employee training, and regular security audits.

Firewalls in Software Engineering

When deploying applications:

- Use security groups in AWS/Azure (virtual firewalls for cloud instances)

- Configure WAFs to protect web applications

- Implement network segmentation (separate database servers from web servers)

- Set up VPNs with firewall rules for remote access

- Monitor firewall logs for suspicious activity

The Load Balancer: Distributing the Workload

You've built an amazing web application. It goes viral. Suddenly, thousands of users are hitting your server simultaneously. Your single server crashes under the load. What do you do?

This is where load balancers save the day.

What is a Load Balancer?

A load balancer is a device or software application that distributes incoming network traffic across multiple servers. It ensures no single server bears too much load, improving availability, reliability, and performance.

Analogy: Imagine a toll plaza on a highway. Instead of forcing all cars through one booth (which would create massive traffic jams), multiple booths operate in parallel, and incoming cars are directed to available booths. The load balancer is the system deciding which car goes to which booth.

Why Scalable Systems Need Load Balancers

Problems Without Load Balancers:

Single Point of Failure: If you have one server handling all requests and it crashes, your entire application goes down. This is unacceptable for production systems.

Overloaded Servers: Every server has limits on concurrent connections and request processing. As traffic grows, a single server becomes a bottleneck.

Limited Scalability: Simply adding more servers doesn't help if all requests still go to the first server. You need a way to distribute traffic.

Poor User Experience: Slow response times and service interruptions drive users away.

Solution: Horizontal Scaling with Load Balancing: Instead of one powerful server (vertical scaling), use multiple modest servers (horizontal scaling) with a load balancer distributing traffic among them.

How Load Balancers Work

The Process:

-

Receive Requests: User requests first arrive at the load balancer, not directly at servers.

-

Health Checks: Load balancer continuously monitors server health (are they responsive? under heavy load?).

-

Distribute Traffic: Based on an algorithm (more on this below), the load balancer forwards each request to the most suitable server.

-

Handle Failures: If a server becomes unresponsive, the load balancer automatically stops sending traffic to it and redistributes to healthy servers.

-

Optimize Performance: By spreading traffic efficiently, load balancers improve overall response times.

Load Balancing Algorithms

Different strategies for choosing which server handles each request:

Round Robin: Distributes requests sequentially across servers in rotation.

Request 1 → Server A

Request 2 → Server B

Request 3 → Server C

Request 4 → Server A (cycle repeats)

Simple, fair, but doesn't consider server load.

Least Connections: Sends requests to the server with the fewest active connections.

Server A: 5 connections

Server B: 3 connections ← Next request goes here

Server C: 7 connections

Better for long-lived connections (WebSockets, database queries).

Least Response Time: Sends requests to the server with the fastest response time and fewest active connections. Optimizes for performance.

IP Hash: Uses the client's IP address to determine which server receives the request. Same client always goes to same server.

hash(client_ip) % number_of_servers = server_index

Useful for session persistence.

Weighted Round Robin: Servers are assigned weights based on capacity. More powerful servers receive more requests.

Server A (weight: 3) gets 3x more requests than

Server B (weight: 1)

Random with Two Choices: Randomly selects two servers and sends the request to the one with fewer connections. Surprisingly effective in practice.

Types of Load Balancers

Layer 4 Load Balancers (Transport Layer):

- Operate at the TCP/UDP level

- Make decisions based on IP addresses and port numbers

- Fast, efficient, but limited intelligence

- Example: AWS Network Load Balancer

Layer 7 Load Balancers (Application Layer):

- Operate at the HTTP/HTTPS level

- Make decisions based on request content (URL, headers, cookies)

- Can route based on API endpoints or user sessions

- More flexible but slightly slower

- Example: AWS Application Load Balancer, NGINX

Hardware Load Balancers:

- Physical devices (expensive, high-performance)

- Used in large enterprises and data centers

Software Load Balancers:

- Applications like NGINX, HAProxy

- Run on standard servers

- More flexible and cost-effective

Cloud Load Balancers:

- Managed services (AWS ELB, Google Cloud Load Balancing, Azure Load Balancer)

- Auto-scaling, high availability, pay-as-you-go

Advanced Load Balancer Features

SSL Termination: Load balancers can handle SSL/TLS encryption/decryption, offloading this CPU-intensive task from backend servers.

Session Persistence (Sticky Sessions): Ensures a user's requests consistently go to the same server during their session. Important for applications that store session data locally.

Health Monitoring: Regular checks (HTTP requests, TCP connections) to detect and remove unhealthy servers from the pool.

Global Server Load Balancing (GSLB): Routes users to the nearest data center based on geographic location. Reduces latency.

Content-Based Routing: Routes traffic based on URL paths:

/api/* → API servers

/images/* → Media servers

/admin/* → Admin servers

Load Balancers in Production

Example: Netflix

Netflix handles millions of concurrent streams. Their architecture uses:

- Load balancers at the edge (AWS ELB)

- Multiple availability zones for redundancy

- Auto-scaling to handle traffic spikes

- Geographic distribution (content delivery networks)

When a user plays a video:

User clicks "Play"

↓

Request hits nearest edge load balancer

↓

Load balancer routes to available streaming server

↓

Server streams video chunks

↓

If server fails, load balancer seamlessly switches to another server

For Your Applications:

- Start with a simple setup (one load balancer, two servers)

- Monitor metrics (request rate, response time, error rate)

- Scale horizontally (add more servers behind the load balancer)

- Use auto-scaling policies in cloud environments

- Implement health checks and graceful shutdowns

Putting It All Together: Real-World Network Architecture

Now that we understand each device individually, let's see how they work together in different scenarios.

Home Network Setup

Internet (from ISP)

↓

[Modem] ← Converts signal from ISP

↓

[Router (with built-in switch and firewall)] ← Creates local network, manages Wi-Fi

↓

Devices: Laptop, Phone, Smart TV, IoT devices

What's Happening:

- ISP sends internet through cable/DSL to your modem

- Modem converts analog signals to digital

- Router receives internet, creates local network

- Router assigns private IPs to devices (DHCP)

- Router's built-in firewall blocks unauthorized access

- Router's switch function allows devices to communicate with each other

- NAT translates between private IPs and public IP

Small Office Network

Internet

↓

[Modem]

↓

[Router]

↓

[Firewall]

↓

[Switch] ← Connects multiple devices

↓

├─ Workstations

├─ Printers

├─ File Server

└─ Wi-Fi Access Points

Additional Components:

- Dedicated firewall for better security

- Managed switch for monitoring and VLANs

- Separate Wi-Fi access points for better coverage

Production Web Application

Users Worldwide

↓

[DNS Service]

↓

[Global Load Balancer]

↓ ↓

[Region 1] [Region 2]

↓ ↓

[Regional LB] [Regional LB]

↓ ↓

[WAF/Firewall] [WAF/Firewall]

↓ ↓

[Application LB] [Application LB]

↓ ↓

┌────────┴────────┐ ┌────────┴────────┐

│ │ │ │

[Web1] [Web2] [Web3] [Web1] [Web2] [Web3]

│ │ │ │

└────────┬────────┘ └────────┬────────┘

↓ ↓

[Internal Firewall] [Internal Firewall]

↓ ↓

[Database LB] [Database LB]

↓ ↓

[Primary DB] [Replica] [Primary DB] [Replica]

Architecture Breakdown:

Layer 1: DNS & Global Load Balancing

- Users connect to your domain (built-from-scratch.vercel.app)

- DNS resolves to nearest region

- Global load balancer routes based on geography

Layer 2: Regional Infrastructure

- Each region has its own load balancers

- Provides redundancy (if one region fails, others continue)

Layer 3: Security

- WAF protects against web attacks

- Firewall rules filter malicious traffic

Layer 4: Application Layer

- Application load balancer distributes across web servers

- Auto-scaling adds/removes servers based on demand

- Health checks ensure only healthy servers receive traffic

Layer 5: Internal Security

- Internal firewall segments web tier from data tier

- Prevents direct access to databases from internet

Layer 6: Data Layer

- Database load balancer manages read/write distribution

- Primary database handles writes

- Replicas handle reads (scaling read-heavy workloads)

How a Request Flows Through the System

Let's trace a single API request:

User types built-from-scratch.vercel.app/api/posts/understanding-network-devices-the-journey-from-internet-to-your-application

↓

1. Browser resolves DNS → Gets IP of global load balancer

↓

2. Request hits global load balancer

↓

3. Global LB routes to nearest region (e.g., us-east-1)

↓

4. Request arrives at regional firewall/WAF

↓

5. WAF inspects request:

- Checks for SQL injection attempts

- Validates request format

- Verifies rate limits

↓

6. Request passes to application load balancer

↓

7. Application LB selects server using least-connections algorithm

↓

8. Request reaches Web Server 2 (has fewest active connections)

↓

9. Web server processes request, needs data from database

↓

10. Internal request goes through internal firewall

↓

11. Database load balancer routes read query to replica

↓

12. Database returns data

↓

13. Response travels back through the chain:

DB → DB LB → Internal FW → Web Server → App LB → WAF → Global LB → User

Total time: < 100ms for a well-optimized system

Key Takeaways for Software Engineers

Understanding these hardware components helps you:

1. Design Better Systems

- Know where to place caching layers

- Understand latency sources

- Design for horizontal scaling

2. Debug Production Issues

- Network timeouts? Check firewall rules.

- Uneven server load? Review load balancer algorithm.

- Slow queries? Database might need a read replica behind a load balancer.

3. Improve Security

- Implement defense in depth (multiple firewall layers)

- Use WAF for web apps

- Segment networks appropriately

4. Optimize Performance

- Use CDNs (global load balancing for static content)

- Implement connection pooling (reduces overhead)

- Choose right load balancing algorithm for your use case

5. Plan for Scale

- Start with simple architecture

- Add load balancers before you need them

- Monitor metrics: request rate, response time, error rate, server health

- Auto-scale based on load

Conclusion

From the modem that connects you to the internet, to the router that manages your local network, to switches that intelligently connect your devices, to firewalls that protect your data, to load balancers that ensure your applications stay online under heavy traffic - each device plays a critical role.

As developers, we might spend most of our time writing code, but understanding the hardware layer gives us superpowers:

- We can diagnose issues faster

- We can design more resilient systems

- We can optimize performance more effectively

- We can communicate better with DevOps and infrastructure teams

The next time you deploy an application, think about the journey your data takes. Every packet passing through modems, routers, switches, firewalls, and load balancers - all working together to deliver your code to users around the world.

That's the beauty of networking: invisible when it works, critical when it doesn't.

Share this post

You Might Also Like

Related posts based on tags, category, and projects

A deep discussion into the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), exploring its architectural origins, the mechanics of the 3-way handshake, and the robust reliability features that underpin the modern internet.

A practical guide to understanding DNS resolution using the dig command, exploring how domain names are translated to IP addresses through root servers, TLD servers, and authoritative nameservers.

Learn how to communicate with servers using cURL, the essential command-line tool every developer needs. This beginner-friendly guide takes you from understanding what servers are to making API requests, with practical examples and common pitfalls to avoid.

Understanding the difference between TCP and UDP protocols, their real-world use cases, and how HTTP actually sits on top of TCP in the networking stack.