TCP 3-Way Handshake & Reliable Communication Explained

A deep discussion into the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), exploring its architectural origins, the mechanics of the 3-way handshake, and the robust reliability features that underpin the modern internet.

Imagine you're trying to send a 500-page manuscript to a friend by throwing single pages out of your window, hoping the wind carries them to your friend's balcony. Without rules, some pages would get lost in a tree, others would arrive out of order, and your friend wouldn't even know if they were missing page 42 or 402.

In the networking world, the "wind" is the Internet Protocol (IP). IP is great at moving packets from point A to point B, but it doesn't care if they arrive in pieces or not at all. It is a "best-effort" delivery service, meaning it makes no guarantees. That’s where TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) comes in. It’s the set of rules the "vigilant manager" that ensures every page is accounted for, put in the right order, and re-sent if it gets stuck in a tree.

What is TCP and Why is it Needed?

TCP was developed by Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn in 1974 as part of the initial network implementation that eventually became the Internet. While IP handles the addressing and routing of packets, TCP provides a reliable, ordered, and error-checked delivery of data between applications.

What this really means is that TCP turns an inherently unreliable network of wires and radio waves into a stable, virtual pipe for data. Major internet applications such as the World Wide Web (HTTP/HTTPS), email (SMTP), and file transfers (FTP) rely heavily on TCP. Without it, your emails might arrive with sentences missing, or your software downloads might be corrupted by a single flipped bit in a router thousands of miles away.

In the OSI model, TCP resides at the Transport Layer (Layer 4). It presents an abstraction of the network to the application, typically through a network socket interface. This means that as a developer, you don't need to worry about the messy details of packet fragmentation, routing paths, or electrical interference; you just open a socket and stream bytes.

The Problem TCP Solves

The internet is a chaotic environment. Routers can become congested and drop packets; physical cables can be damaged; and packets can take different routes, arriving at the destination in a completely different order than they were sent. Without TCP, every application (from your web browser to your email client) would have to reinvent the wheel to handle these failures. TCP standardizes these solutions so developers can focus on building features rather than debugging network noise.

Architecture: OSI vs. TCP/IP Model

Before we dive into the handshake, it's worth noting where TCP fits in the broader architecture. While the OSI model uses seven layers, the TCP/IP model (often called the DoD model) simplifies this into four layers that better reflect how the Internet actually functions.

-

Application Layer: Where protocols like HTTP, SMTP, and FTP live. This layer handles the actual data the user interacts with.

-

Transport Layer: This is TCP’s home. It handles end-to-end communication, reliability, and flow control. It sits between the user's data and the network's delivery system.

-

Internet Layer: Home to IP. It handles packet routing and addressing across different networks, ensuring a packet knows how to get from a server in London to a laptop in Mumbai.

-

Network Interface Layer: Handles the physical transmission of bits over hardware like Ethernet cables, Wi-Fi antennas, or fiber optics.

As data travels down the stack, it undergoes "encapsulation." An HTTP request becomes the payload for a TCP segment, which becomes the payload for an IP datagram, which finally becomes the payload for an Ethernet frame. At the receiving end, the process is reversed decapsulation until the original data reaches the application.

The 3-Way Handshake: Establishing Trust

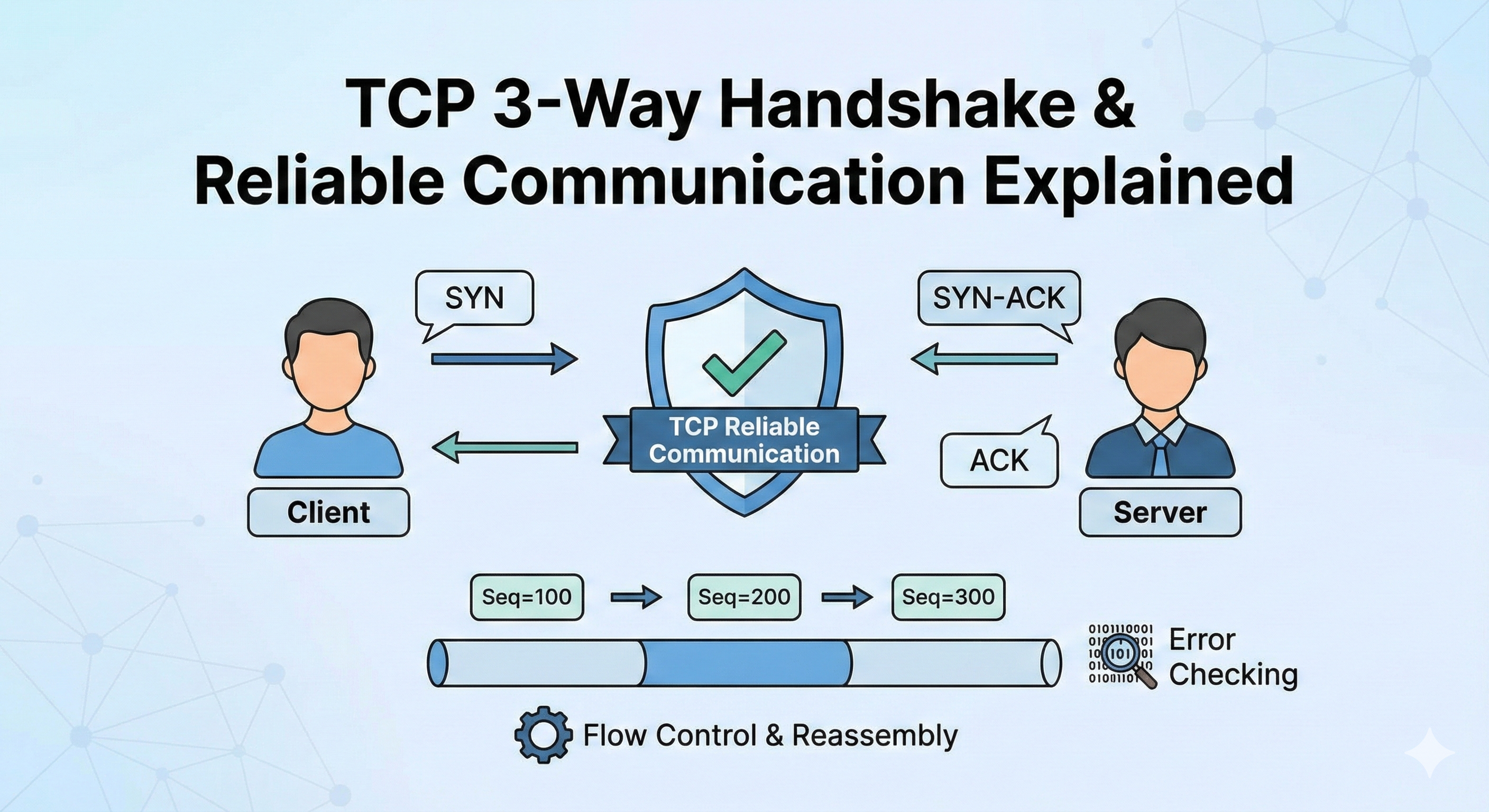

TCP is connection-oriented. This means before any application data is sent, the sender and receiver must agree on parameters. They do this through the 3-Way Handshake.

The Phone Call Analogy

Think of the handshake like a phone call:

- Client: Calls the server. "Hello? Can you hear me?" (SYN)

- Server: Picks up. "Yes, I hear you! Can you hear me?" (SYN-ACK)

- Client: "Yes, I can hear you too. Let's talk." (ACK)

Step-by-Step Technical Breakdown

-

The SYN (Synchronize)

The client initiates an Active Open by sending a segment with the SYN flag set. It chooses a random Initial Sequence Number (ISN), let's call it

X.- Purpose: To synchronize sequence numbers between the two devices. Choosing a random ISN is a security measure to prevent "Sequence Prediction Attacks," where an attacker could inject data into a stream by guessing the next number.

- State: The client enters the

SYN_SENTstate.

-

The SYN-ACK (Synchronize-Acknowledge)

The server, which must be in a Passive Open (listening) state, receives the SYN. It responds with a segment that has both the SYN and ACK flags set.

- Acknowledgment: It sets the

Acknowledgment NumbertoX + 1, telling the client, "I received everything up to X, and I'm ready for X+1." - Sequence Number: The server picks its own random ISN, let's call it

Y. - State: The server enters the

SYN_RCVDstate.

- Acknowledgment: It sets the

-

The ACK (Acknowledge)

The client receives the SYN-ACK and sends one final ACK segment.

-

Acknowledgment: It sets the

Acknowledgment NumbertoY + 1. -

Sequence Number: It uses

X + 1. -

State: Both the client and server enter the

ESTABLISHEDstate. Full-duplex communication (sending and receiving at the same time) is now possible.

-

Why three steps?

A two-way handshake is insufficient because it doesn't confirm that the client received the server's acknowledgment. In a two-way system, if the server's response is delayed and then arrives after the client has given up, the server might hold open a connection that the client no longer cares about, wasting resources.

Handshake Flow Diagram

CLIENT (Active Open) SERVER (Passive Open)

| |

| -------- SYN (Seq=X) -----------------> | (Client: SYN_SENT)

| | (Server: SYN_RCVD)

| <------- SYN-ACK (Seq=Y, Ack=X+1) ----- |

| |

| -------- ACK (Seq=X+1, Ack=Y+1) ------> | (Both: ESTABLISHED)

| |

Data Transfer: Ensuring Reliability

Once established, TCP must maintain its promise of "reliable byte stream delivery." It uses several complex mechanisms to achieve this.

1. Sequence Numbers & Reassembly

TCP doesn't just send files; it sends a stream of bytes. Each byte is numbered. If a 1000-byte file is sent in two 500-byte segments, the first segment has Seq=1, and the second has Seq=501.

-

If segments arrive out of order: The receiver looks at the sequence numbers and places them in the correct buffer position.

-

If a duplicate arrives: TCP recognizes the sequence number has already been processed and discards the extra copy.

2. Positive Acknowledgment with Retransmission (PAR)

The sender keeps a record of every segment it sends. It starts a Retransmission Timeout (RTO) timer. This timer is dynamic; TCP measures the Round Trip Time (RTT) how long it takes for a packet to go out and an ACK to come back and adjusts the timer accordingly.

-

If the receiver gets a segment, it sends an ACK back.

-

If the sender's timer runs out before an ACK is received, it assumes the packet was lost or corrupted and sends it again.

3. Error Detection (Checksums)

Every TCP segment contains a Checksum field. The receiver recalculates this checksum upon arrival. If the result doesn't match the sender's checksum, the segment is considered corrupted and is silently discarded. TCP then relies on the retransmission timer to send a fresh, clean copy.

4. Flow Control: The Sliding Window

A fast sender can easily overwhelm a slow receiver. TCP uses a "Sliding Window" mechanism to prevent this.

- The receiver advertises a

Window Sizein its ACKs. - This number tells the sender: "I only have room for $N$ more bytes in my buffer."

- The sender must stop transmitting once it has $N$ unacknowledged bytes in flight. This ensures the receiver’s buffer never overflows, even if the application is slow to process data.

5. Congestion Control: Protecting the Network

While Flow Control protects the receiver, Congestion Control protects the network. If too many packets are dropped, TCP assumes the network is congested and enters a "Slow Start" phase. It gradually increases the rate of data transmission (the congestion window) until it finds a stable speed. If congestion is detected again, it cuts the window size in half and starts the process over. This "additive increase, multiplicative decrease" (AIMD) approach is what keeps the global internet from collapsing under its own traffic.

SENDER RECEIVER

| --- Segment 1 (Seq=100) ----------> |

| |

| --- Segment 2 (Seq=200) -- [LOST] - |

| |

| <------- ACK (Ack=200) ------------ | (Receiver: "I'm still waiting for 200")

| |

| (RTO Timer for Seq 200 Expires...) |

| |

| --- Segment 2 (Seq=200) [RE-SENT] -> |

| |

| <------- ACK (Ack=300) ------------ | (Receiver: "Got it! Send 300 next")

Closing the Connection: The 4-Way Handshake

Unlike the establishment phase, termination is a 4-step process. This is because TCP is full-duplex, and one side might finish sending data while the other still has more to say. This is known as a Half-Close.

-

FIN (Finish): The host that is done sending data (let's say the Client) sends a FIN segment.

-

ACK: The Server receives the FIN and sends an ACK. The Client can no longer send data, but it can still receive data from the Server.

-

FIN: Once the Server is also done sending data, it sends its own FIN segment.

-

ACK: The Client receives the Server's FIN and sends the final ACK.

The TIME_WAIT State

After the final ACK, the client doesn't immediately disappear. it enters a TIME_WAIT state (usually lasting 2 minutes). This is critical for two reasons:

-

Resending ACKs: If the final ACK was lost, the server will resend its FIN. If the client had already closed, the server would receive an error (RST) and think the connection failed.

-

Port Reuse: It prevents "ghost packets" from an old connection from interfering with a new one on the same port.

Security Vulnerabilities in TCP

Despite its reliability, TCP has several known weaknesses that attackers exploit:

1. SYN Flood (DoS Attack)

An attacker sends thousands of SYN requests but never sends the final ACK. The server creates "half-open" connections for each, eventually running out of memory and crashing. Modern servers use SYN Cookies to mitigate this by not allocating memory until the final ACK arrives.

2. Sequence Prediction Attacks

If an attacker can guess the next sequence number in a handshake, they can inject malicious data into a stream or hijack a session entirely. This is why modern operating systems use high-entropy random number generators for their ISNs.

3. Reset (RST) Attacks

An attacker sends a packet with the RST flag set, mimicking one of the parties. This immediately kills the connection. This is often used by censors to block specific websites or by malicious actors to disrupt communications.

Summary and Key Takeaways

TCP is the backbone of the internet because it provides a predictable, reliable environment in an unpredictable world.

- The 3-Way Handshake ensures both parties are ready and synchronized before a single byte of application data is moved.

- Sequence Numbers allow for reassembly and deduplication, turning fragments into a cohesive file.

- Acknowledgements and Retransmissions guarantee that data eventually arrives, even if the network is flaky.

- Flow and Congestion Control keep the internet from collapsing under its own weight by balancing sender speed with network capacity.

While protocols like UDP are faster because they skip these checks, they lack the "peace of mind" that TCP offers. For the web, email, and file transfers, reliability isn't just a feature it's a requirement.

Share this post

You Might Also Like

Related posts based on tags, category, and projects

Understanding the difference between TCP and UDP protocols, their real-world use cases, and how HTTP actually sits on top of TCP in the networking stack.

Ever wondered how data travels from the internet to your laptop, or how Netflix handles millions of requests without crashing? This deep dive explores the essential networking hardware that makes modern internet possible - modems, routers, switches, hubs, firewalls, and load balancers - and shows how they work together in real-world systems.

A practical guide to understanding DNS resolution using the dig command, exploring how domain names are translated to IP addresses through root servers, TLD servers, and authoritative nameservers.

Ever wondered how your browser knows exactly where to find a website? Learn how DNS records work as the internet's address book, translating domain names into destinations. This beginner-friendly guide explains A, AAAA, CNAME, MX, NS, and TXT records without the jargon.