Talking to Machines: A Complete Guide to cURL for Beginners

Learn how to communicate with servers using cURL, the essential command-line tool every developer needs. This beginner-friendly guide takes you from understanding what servers are to making API requests, with practical examples and common pitfalls to avoid.

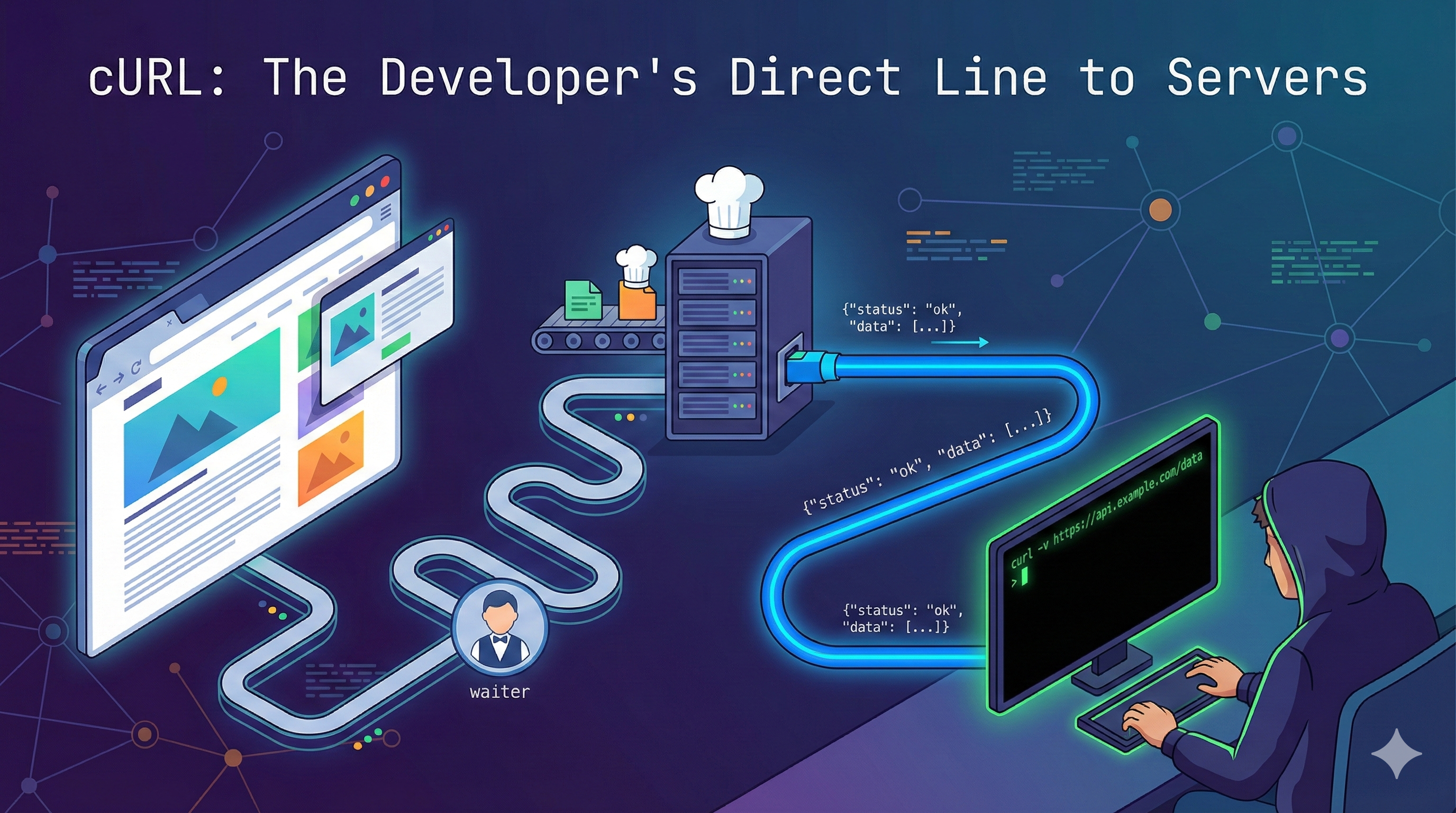

Every time you load a webpage, watch a video, or send a message, your device is having a conversation with another computer somewhere in the world. Usually, your browser handles this conversation for you, translating clicks and taps into requests and turning the responses into beautiful interfaces. But as a developer, you need to understand and control this conversation directly. That's where cURL comes in.

Understanding Servers: The Foundation

Before we talk about cURL, let's understand what we're actually talking to.

What is a Server?

A server is simply a computer that provides services or resources to other computers. When you visit a website, you're connecting to a web server. When you save a file to the cloud, you're talking to a file server. When you use an app on your phone, it's probably communicating with an application server.

Think of it like this: a server is like a restaurant kitchen. You (the client) place an order, and the kitchen (server) prepares your food and sends it back to you. You don't need to know how the kitchen works internally - you just need to know how to order.

The Client-Server Conversation

Every web interaction follows a request-response pattern:

Client (Your Computer)

↓

[Request] → "Give me the homepage"

↓

Server

↓

[Response] ← "Here's the HTML, CSS, and images"

↓

Client (Renders the page)

Your browser is a client. It sends requests and processes responses. But what if you want to send requests without opening a browser? What if you want to automate this process, test your own server, or see the raw data without any visual rendering?

That's exactly why we need cURL.

What is cURL? (In Very Simple Terms)

cURL stands for "Client URL" (though some say it's just "curl"). It's a command-line tool that lets you transfer data to or from a server using various protocols like HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, and more.

Think of cURL as a messenger robot that you can send from your terminal to talk to servers. Unlike a browser, which is designed to make things look pretty for humans, cURL is designed to give developers raw, unfiltered access to server responses.

The Difference: Browser vs cURL

Let's visualize the difference:

Browser Request Flow:

You → Click a link

→ Browser formats the request

→ Browser adds cookies, headers, etc.

→ Browser sends request to server

→ Server responds

→ Browser parses HTML, CSS, JavaScript

→ Browser renders a beautiful page

→ You see: Pretty website

cURL Request Flow:

You → Type a curl command

→ cURL sends request exactly as you specify

→ Server responds

→ cURL prints raw response to terminal

→ You see: Raw HTML/JSON/data

Analogy: If a browser is like dining at a restaurant (you get a nicely plated meal), cURL is like working in the kitchen (you see exactly what ingredients go in and how they're prepared).

Why Programmers Need cURL

You might be thinking: "I have a browser. Why complicate things with terminal commands?"

Here's why cURL is essential in a developer's toolkit:

1. Testing APIs Without a UI

When you build a backend API, you need to test it before building a frontend. cURL lets you send requests instantly from your terminal.

bash1# Test your local API endpoint 2curl http://localhost:3000/api/users

Instead of building a whole form just to test if your endpoint works, you can verify it in seconds with cURL.

2. Automation and Scripting

You can put cURL commands in scripts to automate repetitive tasks:

bash1# Daily health check script 2curl https://myapp.com/health 3curl https://api.myapp.com/status 4curl https://database.myapp.com/ping

Run this script every morning to check if all your services are up.

3. Debugging Production Issues

When something breaks in production, you need to see the raw server response without browser caching, extensions, or other interference. cURL gives you the truth.

4. No Graphical Overhead

cURL doesn't download images, doesn't execute JavaScript, doesn't render CSS. It just fetches data. This makes it:

- Fast

- Lightweight

- Perfect for servers (which don't have browsers)

- Great for CI/CD pipelines

5. Platform Independence

cURL works identically on Windows, macOS, and Linux. Your commands are portable across environments.

6. Learning HTTP Protocol

Using cURL forces you to understand how HTTP actually works - headers, methods, status codes, and request bodies. This knowledge makes you a better developer.

Making Your First Request

Enough theory. Let's get our hands dirty.

Installing cURL

Most systems come with cURL pre-installed. Check if you have it:

bash1curl --version

If you see version information, you're good to go. If not:

- macOS: Usually pre-installed. If not, install via Homebrew:

brew install curl - Linux:

sudo apt install curl(Ubuntu/Debian) orsudo yum install curl(RHEL/CentOS) - Windows: Comes with Windows 10+ or download from curl.se

The Simplest Request

Open your terminal and type:

bash1curl https://chaicode.com

Hit enter. You'll see a wall of HTML code flood your terminal. Congratulations! You just made your first HTTP request using cURL.

What happened?

- cURL connected to chaicode.com's server

- It sent an HTTP GET request asking for the homepage

- The server responded with HTML

- cURL printed that HTML to your terminal

Making It Readable

Raw HTML is hard to read. Let's try fetching some JSON data instead:

bash1curl https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts/1

You'll see something like:

json1{ 2 "userId": 1, 3 "id": 1, 4 "title": "sunt aut facere repellat provident", 5 "body": "quia et suscipit\nsuscipit..." 6}

Much better! You just fetched data from a REST API - the same way your applications do it.

Understanding Request and Response

Every HTTP interaction has two parts: the request you send and the response you get back. Let's break down what's actually happening.

The HTTP Request Structure

When cURL sends a request, it includes several components:

GET /posts/1 HTTP/1.1 ← Request line (method, path, protocol)

Host: jsonplaceholder.typicode.com ← Headers

User-Agent: curl/7.64.1

Accept: */*

[Request body - empty for GET requests]

Let's see this in action:

bash1curl -v https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts/1

The -v (verbose) flag shows you everything cURL sends and receives. You'll see:

>lines: What cURL sends to the server<lines: What the server sends back

The HTTP Response Structure

The server's response has three parts:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK ← Status line

Content-Type: application/json ← Headers

Date: Mon, 20 Jan 2026 10:30:00 GMT

Content-Length: 292

{ ← Body (the actual data)

"userId": 1,

"id": 1,

...

}

HTTP Status Codes: What They Mean

The status code tells you if your request succeeded:

- 2xx (Success):

200 OK- Request succeeded201 Created- Resource was created successfully

- 3xx (Redirection):

301 Moved Permanently- Resource moved to new URL304 Not Modified- Cached version is still valid

- 4xx (Client Error):

400 Bad Request- Your request was malformed401 Unauthorized- You need to authenticate404 Not Found- Resource doesn't exist

- 5xx (Server Error):

500 Internal Server Error- Server crashed503 Service Unavailable- Server is down or overloaded

Check just the status code:

bash1curl -I https://www.google.com

The -I flag fetches headers only (no body), which includes the status code.

Using cURL to Talk to APIs

Modern web development revolves around APIs - Application Programming Interfaces. These are servers that speak in data (usually JSON) rather than HTML. Let's learn how to interact with them.

The GET Request: Fetching Data

GET is the default HTTP method. It's used to retrieve information without modifying anything on the server.

Basic GET request:

bash1curl https://api.github.com/users/atharvdange618

This fetches my github user data.

GET with query parameters:

APIs often accept parameters to filter or customize responses:

bash1curl "https://api.github.com/search/repositories?q=javascript&sort=stars"

Note the quotes around the URL. This is crucial when URLs contain special characters like &, ?, or =.

Why quotes matter:

bash1# WRONG - shell interprets & as background process 2curl https://api.com?name=john&age=25 3 4# RIGHT - quotes protect the URL 5curl "https://api.com?name=john&age=25"

The POST Request: Sending Data

POST is used to send data to the server, typically to create new resources.

Basic POST with data:

bash1curl -X POST -d "title=Hello World&body=This is my post" \ 2 https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts

Let's break this down:

-X POST: Specifies the HTTP method-d: Sends data (the-dflag automatically sets method to POST, so-X POSTis optional here)

POST with JSON:

Most modern APIs expect JSON. Here's how to send it:

bash1curl -X POST \ 2 -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ 3 -d '{"title":"Hello","body":"World"}' \ 4 https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts

-H: Adds a headerContent-Type: application/json: Tells server you're sending JSON- The data is wrapped in single quotes to preserve the JSON structure

Authentication: Sending Credentials

Many APIs require authentication. Here are common patterns:

Basic authentication:

bash1curl -u username:password https://api.example.com/data

Bearer token (JWT):

bash1curl -H "Authorization: Bearer YOUR_TOKEN_HERE" \ 2 https://api.example.com/protected

API Key in header:

bash1curl -H "X-API-Key: your-api-key" \ 2 https://api.example.com/data

Saving Responses to Files

Instead of printing to terminal, save responses:

bash1# Using -o (output) flag 2curl -o response.json https://api.github.com/users/atharvdange618 3 4# Using -O (capital O) - saves with remote filename 5curl -O https://example.com/file.pdf

Following Redirects

Some URLs redirect to other locations. Use -L to follow them:

bash1curl -L https://github.com

Without -L, cURL stops at the redirect and you get the redirect response instead of the final page.

Common Mistakes Beginners Make

Learning from others' mistakes is faster than making them yourself. Here are the most common cURL pitfalls:

1. Forgetting the Protocol

bash1# WRONG 2curl google.com 3 4# RIGHT 5curl https://google.com

cURL needs to know what protocol to use. Always include http:// or https://.

2. Unquoted URLs with Special Characters

bash1# WRONG - shell breaks on & 2curl https://api.com/search?q=javascript&sort=stars 3 4# RIGHT 5curl "https://api.com/search?q=javascript&sort=stars"

Characters like &, ?, =, #, and spaces have special meaning in shells. Quote your URLs.

3. Mismatched or Unclosed Quotes

bash1# WRONG - unclosed quote 2curl -d '{"name": "John}' 3 4# RIGHT 5curl -d '{"name": "John"}'

If you start with a single quote, you must end with a single quote. If you start with double quotes, end with double quotes.

Pro tip: Use single quotes for JSON to avoid escaping double quotes inside the JSON.

4. Ignoring Status Codes

bash1curl https://api.example.com/endpoint

Just because cURL doesn't show an error doesn't mean the request succeeded. The server might have returned a 404 or 500. Always check:

bash1curl -w "\nHTTP Status: %{http_code}\n" https://api.example.com/endpoint

The -w flag adds custom output formatting. %{http_code} prints the HTTP status code.

5. Not Checking Verbose Output

When something doesn't work, don't guess. Use verbose mode:

bash1curl -v https://api.example.com/endpoint

This shows you:

- DNS resolution

- Connection details

- SSL handshake (for HTTPS)

- Full request headers

- Full response headers

6. Forgetting Content-Type Headers

bash1# WRONG - server doesn't know you're sending JSON 2curl -X POST -d '{"name":"John"}' https://api.com/users 3 4# RIGHT 5curl -X POST \ 6 -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ 7 -d '{"name":"John"}' \ 8 https://api.com/users

Servers need the Content-Type header to parse your data correctly.

7. Using GET When You Need POST

bash1# This sends data but uses GET (won't work as expected) 2curl "https://api.com/create?name=John&email=john@example.com" 3 4# This properly sends data with POST 5curl -X POST \ 6 -d "name=John&email=john@example.com" \ 7 https://api.com/create

GET requests should fetch data. POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE should modify data.

8. Not Handling Spaces in Data

bash1# WRONG - shell breaks on spaces 2curl -d title=Hello World https://api.com/posts 3 4# RIGHT 5curl -d "title=Hello World" https://api.com/posts

Where cURL Fits in Backend Development

Now that you know how to use cURL, let's understand its role in modern development workflows.

Testing Your Own APIs

When building a REST API, cURL is your first testing tool:

bash1# Start your server locally 2npm start 3 4# In another terminal, test endpoints 5curl http://localhost:3000/api/health 6curl http://localhost:3000/api/users 7curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ 8 -d '{"name":"Test"}' http://localhost:3000/api/users

This is faster than:

- Building a frontend

- Opening Postman

- Writing automated tests

CI/CD Pipelines

In deployment scripts, cURL verifies services are healthy:

bash1# deploy.sh 2echo "Deploying application..." 3# ... deployment code ... 4 5echo "Checking if service is up..." 6STATUS=$(curl -s -o /dev/null -w "%{http_code}" https://myapp.com/health) 7 8if [ $STATUS -eq 200 ]; then 9 echo "Deployment successful!" 10else 11 echo "Deployment failed - service not responding" 12 exit 1 13fi

Monitoring and Alerting

Check if your services are alive:

bash1# healthcheck.sh 2curl -f https://api.myapp.com/health || \ 3 curl -X POST https://slack.com/webhook \ 4 -d '{"text":"API is down!"}'

The -f flag makes cURL exit with error code on HTTP errors, which triggers the alert.

Webhooks and Integration Testing

Trigger webhooks manually:

bash1curl -X POST https://myapp.com/webhooks/github \ 2 -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ 3 -d '{"event":"push","repository":"myrepo"}'

Downloading and Uploading Files

bash1# Download a file 2curl -O https://example.com/file.zip 3 4# Upload a file 5curl -X POST -F "file=@document.pdf" \ 6 https://api.example.com/upload

Practical Examples: Putting It All Together

Let's work through real-world scenarios.

Example 1: Testing a Login Endpoint

bash1# Send login credentials 2curl -X POST \ 3 -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ 4 -d '{"email":"user@example.com","password":"secret"}' \ 5 https://api.example.com/login 6 7# Response might include a token 8{ 9 "token": "eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9...", 10 "user": {"id": 1, "email": "user@example.com"} 11} 12 13# Use that token in subsequent requests 14curl -H "Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9..." \ 15 https://api.example.com/profile

Example 2: Creating a GitHub Issue

bash1curl -X POST \ 2 -H "Authorization: token YOUR_GITHUB_TOKEN" \ 3 -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ 4 -d '{"title":"Bug report","body":"Something is broken"}' \ 5 https://api.github.com/repos/username/repo/issues

Example 3: Weather API Query

bash1curl "https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=London&appid=YOUR_API_KEY"

Example 4: Testing Rate Limits

bash1# Make 10 requests and see when you get rate limited 2for i in {1..10}; do 3 echo "Request $i:" 4 curl -w "Status: %{http_code}\n" \ 5 -H "Authorization: Bearer TOKEN" \ 6 https://api.example.com/data 7 echo "---" 8done

Beyond the Basics: Next Steps

Once you're comfortable with basic cURL, explore these advanced features:

Custom Headers

bash1curl -H "User-Agent: MyApp/1.0" \ 2 -H "Accept-Language: en-US" \ 3 https://api.example.com

Cookies

bash1# Save cookies 2curl -c cookies.txt https://example.com/login 3 4# Use saved cookies 5curl -b cookies.txt https://example.com/dashboard

Timeouts

bash1# Fail if connection takes longer than 5 seconds 2curl --connect-timeout 5 https://slow-server.com

Retry Logic

bash1# Retry up to 3 times with 2-second intervals 2curl --retry 3 --retry-delay 2 https://unreliable-api.com

The Big Picture

cURL is more than just a tool - it's a window into how the internet actually works. Every time you use it, you're operating at the same level as browsers, mobile apps, and IoT devices. You're speaking HTTP directly.

Understanding cURL makes you better at:

- Debugging API issues

- Writing backend services

- Understanding frontend-backend communication

- Troubleshooting network problems

- Reading API documentation

- Building automation scripts

It's one of those tools that seems simple on the surface but has incredible depth. You can spend five minutes learning the basics or five years mastering every flag and option - and both are time well spent.

Quick Reference Cheat Sheet

bash1# Basic GET 2curl https://api.example.com/data 3 4# GET with headers 5curl -H "Authorization: Bearer TOKEN" https://api.example.com/data 6 7# POST with JSON 8curl -X POST \ 9 -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ 10 -d '{"key":"value"}' \ 11 https://api.example.com/data 12 13# POST with form data 14curl -X POST -d "name=John&age=30" https://api.example.com/form 15 16# Save response to file 17curl -o output.json https://api.example.com/data 18 19# Show only headers 20curl -I https://api.example.com 21 22# Follow redirects 23curl -L https://example.com 24 25# Verbose output (debugging) 26curl -v https://api.example.com 27 28# Show HTTP status code 29curl -w "\nHTTP: %{http_code}\n" https://api.example.com 30 31# Upload file 32curl -X POST -F "file=@document.pdf" https://api.example.com/upload

Final Thoughts

When I first started learning backend development, cURL felt intimidating. All those flags, the raw output, the terminal commands - it seemed unnecessary when I could just use a browser or Postman. But here's what I learned: cURL teaches you to think like a server.

It strips away all the visual sugar and forces you to understand the underlying protocol. Once you get comfortable with cURL, you'll find yourself reaching for it constantly. It becomes second nature.

Start simple. Make a GET request. Then try POST. Gradually add headers and authentication. Before you know it, you'll be debugging production issues, writing deployment scripts, and testing APIs like a pro - all from the comfort of your terminal.

The internet is just computers talking to each other. Now you know how to join the conversation.

Share this post

You Might Also Like

Related posts based on tags, category, and projects

Understanding the difference between TCP and UDP protocols, their real-world use cases, and how HTTP actually sits on top of TCP in the networking stack.

Ever wondered how data travels from the internet to your laptop, or how Netflix handles millions of requests without crashing? This deep dive explores the essential networking hardware that makes modern internet possible - modems, routers, switches, hubs, firewalls, and load balancers - and shows how they work together in real-world systems.

A friend complained about eye strain from reading white-backgrounded PDFs at night. What started as a simple CSS fix turned into building a custom PDF text extraction and rendering system in bare React Native when every existing library failed.

A deep discussion into the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), exploring its architectural origins, the mechanics of the 3-way handshake, and the robust reliability features that underpin the modern internet.