Understanding HTML Tags and Elements

A complete guide to HTML tags and elements, explaining the difference between the two, how they work together to structure web pages, and the most common patterns you'll use every day as a developer.

If you've ever opened your browser's developer tools and looked at a website's code, you've seen HTML. It looks like a bunch of angle brackets with words inside them, wrapping around text and other content. But here's the thing: understanding what those brackets actually mean and how they work together is fundamental to everything else you'll do in web development.

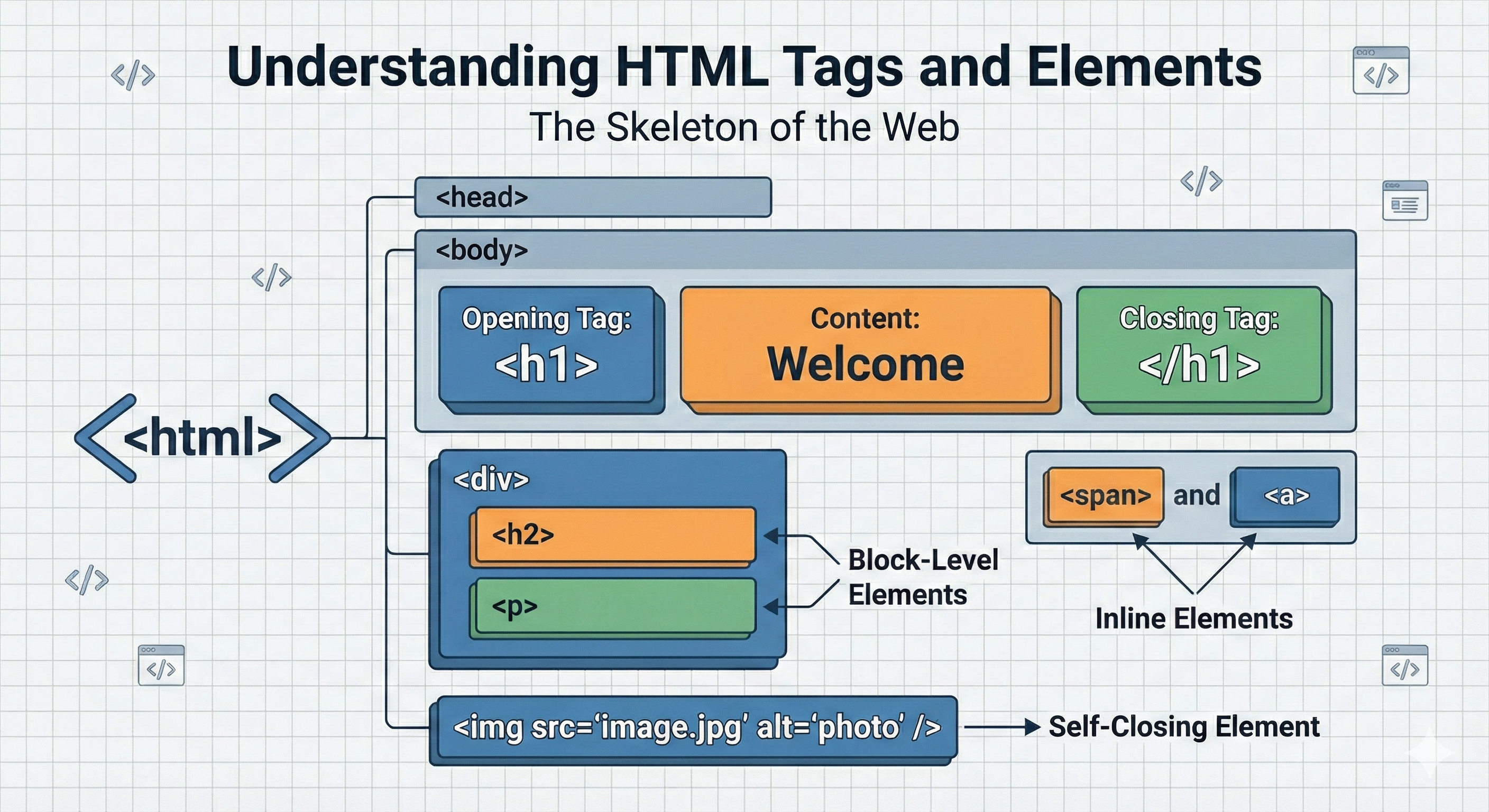

Think of HTML as the skeleton of every webpage you've ever visited. Without it, there's no structure, no way for the browser to understand what's a heading versus what's a paragraph, or where an image should go. CSS makes things pretty, JavaScript makes them interactive, but HTML is what holds everything together in the first place.

What HTML Actually Is and Why We Need It

HTML stands for HyperText Markup Language. Let's break that down because each word matters. HyperText means it can link to other documents (that's the whole web in a nutshell). Markup means you're marking up plain text with extra information about its structure and meaning. And Language means it has syntax and rules the browser understands.

When you write HTML, you're essentially having a conversation with the browser. You're telling it "this chunk of text is a heading, make it big and bold" or "this is a link, make it clickable." The browser reads your HTML and turns it into the visual webpage you see.

Here's what makes HTML critical: browsers need structure to render content properly. Without HTML telling the browser what's what, all you'd have is a wall of text with no hierarchy, no images, no links, nothing. HTML provides the semantic structure that makes the web actually work.

What an HTML Tag Is

A tag is like a label you attach to content. Think of it as wrapping a piece of text in a container that tells the browser what kind of content it is. Tags use angle brackets (less-than and greater-than symbols) to distinguish themselves from regular text.

Let's look at the anatomy of a tag:

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ <p>This is a paragraph.</p> │

│ ↑↑↑ ↑↑↑↑ │

│ │││ ││││ │

│ Opening tag Closing tag │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

An opening tag starts with < followed by the tag name, then >. A closing tag is almost identical except it has a forward slash / right after the opening bracket: </tagname>.

The tag name tells the browser what type of content you're marking up. The letter p stands for paragraph. When the browser sees <p>, it knows to start a new paragraph. When it sees </p>, it knows the paragraph is done.

Here's a simple example:

html1<h1>Welcome to My Blog</h1>

The opening tag is <h1> (which means heading level 1, the biggest heading). The closing tag is </h1>. Together, they wrap around the text "Welcome to My Blog" to tell the browser this text should be displayed as a main heading.

Opening Tags, Closing Tags, and Content

Most HTML tags come in pairs: an opening tag and a closing tag. Everything between those two tags is the content. This pattern is so common you'll write it thousands of times, so it's worth understanding deeply.

Here's the structure:

Opening Tag + Content + Closing Tag = Complete Pattern

<tagname>Content goes here</tagname>

The content can be plain text, other HTML elements, or a mix of both. Let's look at a real example:

html1<p>This is a simple paragraph with just text.</p> 2 3<div> 4 <h2>A Section Heading</h2> 5 <p>This div contains multiple elements inside it.</p> 6</div>

In the first example, the content is just the text "This is a simple paragraph with just text." In the second example, the div element's content includes two other complete elements (an h2 and a p), each with their own content.

What this really means is that HTML is nestable. You can put elements inside other elements, creating a tree-like structure. The browser understands this hierarchy and uses it to figure out how elements relate to each other.

One crucial rule: tags must be properly nested. If you open tag A, then open tag B, you must close tag B before you close tag A. Think of it like parentheses in math they have to match up correctly.

html1<!-- Correct nesting --> 2<div><p>Good!</p></div> 3 4<!-- Incorrect nesting --> 5<div><p>Bad!</div></p>

The Difference Between Tags and Elements

Here's where things click together. A tag is just the markup itself the <p> or </p>. An element is the complete package: opening tag, content, and closing tag all together.

Let me show you the breakdown:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ THE COMPLETE ELEMENT │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ <p>This is a paragraph.</p> │ │

│ │ ↑ ↑ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ Opening Tag Closing Tag │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Content: "This is a │ │

│ │ paragraph." │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Tags: <p> and </p>

Element: The whole thing including content

When developers say "add a paragraph element to your HTML," they mean write the complete thing with opening tag, content, and closing tag. When they say "use the p tag," they're being a bit informal but usually mean the same thing.

This distinction matters when you start learning about the DOM (Document Object Model) and JavaScript. In JavaScript, you'll manipulate elements, not just tags. An element is an object in the browser's memory that represents that whole chunk of HTML.

Self-Closing Elements (Void Elements)

Not every element follows the opening-closing tag pattern. Some elements don't have any content, so they don't need a closing tag. These are called void elements or self-closing elements.

The most common void elements are:

html1<img src="photo.jpg" alt="A description" /> 2<br /> 3<hr /> 4<input type="text" /> 5<meta charset="UTF-8" /> 6<link rel="stylesheet" href="styles.css" />

Notice how these don't have closing tags? An image element, for example, doesn't contain text content between tags. Instead, it has attributes (like src and alt) that tell it what to display and how to behave.

You might see some HTML written like this:

html1<img src="photo.jpg" alt="A description" />

That trailing slash before the closing bracket is optional in HTML5 but required in XHTML (a stricter version of HTML). Most developers skip it these days, but you'll see both styles in the wild.

Here's the key insight: void elements represent things that are complete in themselves. An image is just an image. A line break is just a break. They don't wrap around content the way a paragraph or heading does.

Block-Level vs Inline Elements

This is where HTML starts affecting visual layout. Elements fall into two main categories based on how they behave on the page: block-level and inline.

Block-level elements start on a new line and take up the full width available. Think of them as claiming an entire horizontal stripe of the page. When you stack block elements, they stack vertically like boxes.

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ <div>First block</div> │ ← Takes full width

├─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ <p>Second block</p> │ ← Starts new line

├─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ <h1>Third block</h1> │ ← Starts new line

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

Common block-level elements:

div(a generic container)p(paragraph)h1throughh6(headings)ul,ol,li(lists)header,footer,section,article(semantic containers)

Inline elements, on the other hand, flow with the text. They only take up as much width as they need and don't force new lines. Multiple inline elements can sit side by side on the same line.

This is a paragraph with <strong>bold text</strong> and

<a href="#">a link</a> that flow naturally with the text.

Visual result:

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ This is a paragraph with bold text │

│ and a link that flow naturally with │

│ the text. │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

Common inline elements:

span(a generic inline container)a(links)strong(bold/important text)em(italic/emphasized text)img(images, though they're actually inline-block)code(inline code snippets)

Here's a practical example showing the difference:

html1<!-- Block elements stack vertically --> 2<div>First div</div> 3<div>Second div</div> 4 5<!-- Inline elements flow together --> 6<p>This <span>span element</span> stays <span>inline</span> with text.</p>

The visual result:

┌─────────────────────────┐

│ First div │

├─────────────────────────┤

│ Second div │

├─────────────────────────┤

│ This span element stays │

│ inline with text. │

└─────────────────────────┘

Understanding this distinction helps you choose the right element for your layout. Need to create separate sections? Use block elements. Need to style a few words in a sentence? Use inline elements.

Commonly Used HTML Tags

Let's walk through the tags you'll use constantly. Instead of just listing them, I'll show you what each one does and when you'd reach for it.

Headings

html1<h1>Main Page Title</h1> 2<h2>Section Heading</h2> 3<h3>Subsection Heading</h3> 4<h4>Smaller Heading</h4> 5<h5>Even Smaller</h5> 6<h6>Smallest Heading</h6>

Headings create hierarchy. Use h1 for the main title of your page (usually only one per page), h2 for major sections, h3 for subsections, and so on. Screen readers use this structure to help users navigate, so don't pick heading levels based on size pick them based on content hierarchy.

Paragraphs

html1<p> 2 A paragraph is a block of text. Each paragraph element creates spacing above 3 and below automatically. This is your bread-and-butter element for regular 4 text content. 5</p>

Links

html1<a href="https://example.com">Click here to visit Example</a> 2<a href="/about">Internal link to about page</a> 3<a href="#section-id">Jump to a section on this page</a>

The href attribute tells the link where to go. Links are inline elements, so they flow with surrounding text.

Images

html1<img src="path/to/image.jpg" alt="Description of the image" />

Always include the alt attribute. It describes the image for screen readers and shows up if the image fails to load. The src attribute points to the image file.

Containers

html1<div> 2 <p> 3 A div is a generic block container. Use it to group related elements 4 together for styling or layout purposes. 5 </p> 6</div> 7 8<span>A span is a generic inline container</span> for styling small chunks of 9text.

Think of div and span as blank containers. They have no special meaning they're just there to help you organize and style content.

Lists

html1<!-- Unordered list (bullets) --> 2<ul> 3 <li>First item</li> 4 <li>Second item</li> 5 <li>Third item</li> 6</ul> 7 8<!-- Ordered list (numbers) --> 9<ol> 10 <li>Step one</li> 11 <li>Step two</li> 12 <li>Step three</li> 13</ol>

Lists need two parts: the container (ul or ol) and the individual items (li). You can't have list items without a list container, and the container doesn't make sense without items.

Text Formatting

html1<strong>This text is important (usually bold)</strong> 2<em>This text is emphasized (usually italic)</em> 3<code>const variable = "inline code";</code> 4<br /> 5<!-- Line break -->

These are all inline elements that add semantic meaning to text. Use strong for important text, em for emphasis, and code for programming terms or commands.

Buttons and Forms

html1<button>Click Me</button> 2 3<input type="text" placeholder="Enter your name" /> 4<input type="email" placeholder="Enter your email" /> 5<input type="password" placeholder="Enter password" />

Buttons and inputs are how users interact with your page. There are many input types, each with different behavior and validation.

Inspecting HTML in the Browser

Here's something that will accelerate your learning: every browser has built-in developer tools that let you see and even edit HTML in real-time. This is how you learn what works and what doesn't.

To open developer tools:

- Chrome/Edge: Press F12 or right-click anywhere and choose "Inspect"

- Firefox: Press F12 or right-click and choose "Inspect Element"

- Safari: Enable developer tools in preferences, then press Cmd+Option+I

Once you have the tools open, you'll see the Elements or Inspector panel showing the HTML structure of the page. Hover over elements in the panel and the browser highlights them on the page. Click an element to see its properties, styles, and more.

Try this exercise: go to any website, open the developer tools, and start exploring. Find a heading and see what tag it uses. Find a button and see how it's structured. Change some text in the inspector (it won't save, so don't worry about breaking anything) and watch it update on the page.

This hands-on exploration teaches you more than reading ever could. You'll start to recognize patterns, see how professional developers structure their HTML, and build an intuition for what works.

Putting It All Together

Let's look at a complete HTML structure that uses everything we've covered:

html1<!DOCTYPE html> 2<html> 3 <head> 4 <title>My First Webpage</title> 5 </head> 6 <body> 7 <h1>Welcome to My Blog</h1> 8 9 <p> 10 This is an introduction paragraph. Notice how it's a 11 <strong>block element</strong> that starts on its own line. 12 </p> 13 14 <h2>About HTML</h2> 15 16 <p> 17 HTML uses tags and elements to structure content. Here are some examples: 18 </p> 19 20 <ul> 21 <li>Headings organize content hierarchically</li> 22 <li>Paragraphs contain text blocks</li> 23 <li>Links connect pages together</li> 24 </ul> 25 26 <div> 27 <h3>Learn More</h3> 28 <p> 29 Check out <a href="https://developer.mozilla.org">MDN Web Docs</a> for 30 comprehensive HTML documentation. 31 </p> 32 <img src="html-logo.png" alt="HTML5 logo" /> 33 </div> 34 </body> 35</html>

Look at how the elements nest inside each other. The body contains everything visible on the page. Inside the body, we have headings, paragraphs, lists, and a div container. The div groups related content together. The list has a container (ul) with individual items (li) inside.

This nesting structure creates a tree that the browser uses to build the page. Each element knows its parent and children, forming relationships that CSS and JavaScript can leverage.

Key Takeaways

HTML is simpler than it looks once you understand the fundamental concepts. Tags are the markers with angle brackets. Elements are the complete package of opening tag, content, and closing tag. Some elements (void elements) don't have content or closing tags because they're self-contained.

Block-level elements stack vertically and take full width. Inline elements flow with text and only take the space they need. Knowing this helps you predict how your HTML will look in the browser.

The tags we covered here headings, paragraphs, links, images, lists, divs, and spans make up the majority of HTML you'll write. Master these fundamentals and everything else becomes easier. Start simple, use your browser's developer tools to experiment, and build up from there.

The beauty of HTML is that you can open a text file, write some tags, save it with an .html extension, and open it in a browser. No compilation, no complex setup. Just markup that instantly becomes a webpage. That simplicity is powerful it means you can start building right now.

Share this post

You Might Also Like

Related posts based on tags, category, and projects

Master the fundamentals of CSS selectors to precisely target and style HTML elements, from basic element selectors to more specific class and ID targeting strategies.

Learn how Emmet transforms HTML writing from tedious typing into powerful abbreviations that expand into complete markup, saving time and reducing errors for beginners and professionals alike.

Ever wondered what happens after you hit Enter in your address bar? This guide breaks down how browsers transform URLs into interactive web pages, covering everything from networking to rendering.

Understanding the difference between TCP and UDP protocols, their real-world use cases, and how HTTP actually sits on top of TCP in the networking stack.