Emmet for HTML: A Beginner's Guide to Writing Faster Markup

Learn how Emmet transforms HTML writing from tedious typing into powerful abbreviations that expand into complete markup, saving time and reducing errors for beginners and professionals alike.

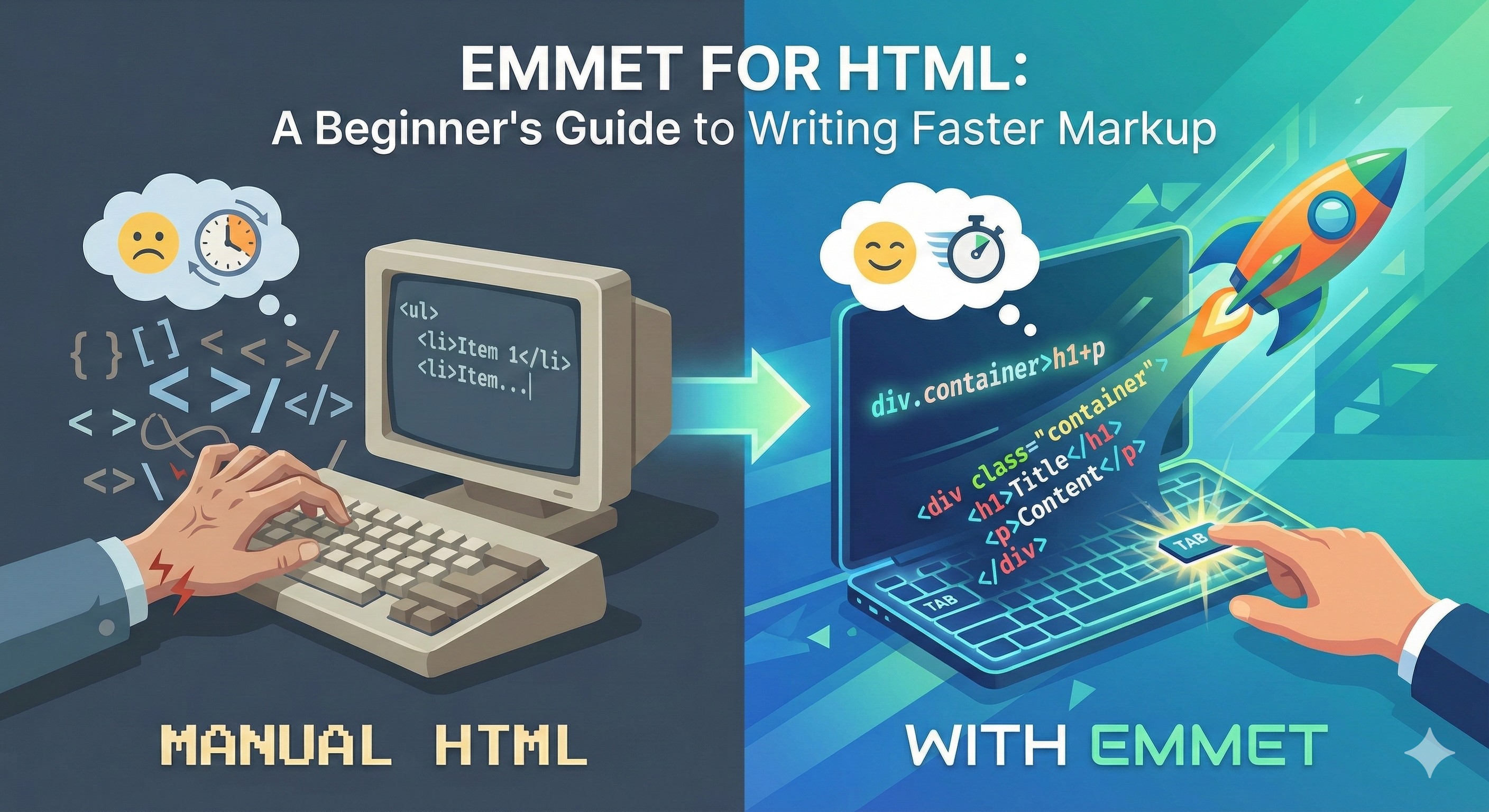

If you've ever typed out HTML by hand, you know the feeling. You're constantly opening and closing tags, adding attributes, nesting elements, and by the time you finish a simple navigation bar, your fingers are tired and you've probably forgotten to close a div somewhere. There's a better way.

Emmet is a toolkit built into most modern code editors that lets you write HTML using shorthand abbreviations. Instead of typing out every single bracket and tag name, you write a compact expression and Emmet expands it into proper HTML. Think of it as autocomplete on steroids, except you're in control of exactly what gets generated.

Why Emmet Matters for Beginners

Here's the thing: when you're learning HTML, you need to understand the structure of elements, how nesting works, and what attributes do. Emmet doesn't replace that learning. What it does is remove the mechanical friction once you know what you want to build.

Without Emmet, creating a simple unordered list with three items means typing something like this:

html1<ul> 2 <li></li> 3 <li></li> 4 <li></li> 5</ul>

With Emmet, you type ul>li*3 and hit Tab or Enter. That's it. The editor expands it into the exact structure above, cursor ready for you to add content.

The benefit isn't just speed. When you're writing abbreviations, you're thinking in terms of structure rather than syntax. You describe what you want and let Emmet handle the brackets and closing tags. This means fewer typos, fewer unclosed tags, and more mental energy for actually designing your page.

How Emmet Works Inside Your Editor

Most code editors today come with Emmet built in. VS Code, WebStorm, Sublime Text, and Atom all support it out of the box. When you're editing an HTML file, Emmet is already listening. You type an abbreviation, then trigger expansion, usually with the Tab key or Enter.

The flow looks like this:

You type: div.container>h1+p

You press: Tab

Editor generates:

<div class="container">

<h1></h1>

<p></p>

</div>

The editor recognizes the pattern, interprets it according to Emmet's syntax rules, and replaces your abbreviation with real HTML. Your cursor automatically moves to the first empty spot where you'd typically add content.

Basic Emmet Syntax

Emmet uses symbols to describe HTML structure. Each symbol has a specific meaning that mirrors how HTML actually works.

The > symbol means "child of". When you write div>p, you're saying "a paragraph inside a div". This is how you create nested elements.

The + symbol means "sibling of". Writing h1+p creates a heading and a paragraph next to each other, not inside each other.

The * symbol means "multiply". If you need five list items, li*5 generates all five without typing each one separately.

Classes use a dot, just like CSS selectors. Writing div.header creates <div class="header"></div>. IDs use a hash: div#main becomes <div id="main"></div>.

Attributes go inside square brackets. For example, a[href="https://example.com"] expands to

<a href="https://example.com"></a>.

You can combine all of these symbols to build complex structures in a single line.

Creating Elements and Adding Classes

Let's start with the simplest case. Type div and press Tab. You get <div></div>. Not particularly impressive, but it's the foundation.

Now type div.card and expand it.

You get <div class="card"></div> . The dot tells Emmet to add a class attribute. Want multiple classes? Just chain them: div.card.featured.highlight produces

<div class="card featured highlight"></div>.

IDs work the same way. Type header#main-header and you'll get <header id="main-header"></header>. You can combine classes and IDs freely: section#about.dark-theme creates

<section id="about" class="dark-theme"></section>.

Here's something useful: if you don't specify an element type but you do specify a class or ID, Emmet assumes you want a div. So .wrapper expands to <div class="wrapper"></div>. This saves time when you're building layouts that use divs heavily.

Building Nested Structures

The real power shows up when you start nesting elements. The > operator creates parent-child relationships.

Type nav>ul>li and expand it:

html1<nav> 2 <ul> 3 <li></li> 4 </ul> 5</nav>

Each > symbol pushes you one level deeper into the structure. This mirrors exactly how HTML nesting works, but you're describing it in shorthand.

Want siblings at the same level? Use the + operator. The abbreviation header+main+footer generates three top-level elements:

html1<header></header> 2<main></main> 3<footer></footer>

You can mix > and + to create complex structures. Here's a common pattern: div.container>header+main+footer. This creates a container div with three children inside it.

html1<div class="container"> 2 <header></header> 3 <main></main> 4 <footer></footer> 5</div>

Multiplying Elements

When you need multiple copies of the same element, the * operator saves enormous amounts of typing. The abbreviation li*3 creates three list items instantly.

This becomes particularly powerful when combined with nesting. The pattern ul>li*5 gives you a complete unordered list with five items:

html1<ul> 2 <li></li> 3 <li></li> 4 <li></li> 5 <li></li> 6 <li></li> 7</ul>

You can use multiplication anywhere in your abbreviation. Want a navigation bar with multiple links? Try nav>ul>li*4>a. This creates a nav element containing an unordered list with four list items, each containing an anchor tag.

Creating the HTML Boilerplate

One of the most practical uses of Emmet is generating the standard HTML5 document structure. When you start a new HTML file, you need the doctype, html tag, head section with meta tags, and body. That's a lot of typing.

With Emmet, type ! or html:5 and press Tab. You instantly get:

html1<!DOCTYPE html> 2<html lang="en"> 3 <head> 4 <meta charset="UTF-8" /> 5 <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" /> 6 <title>Document</title> 7 </head> 8 <body></body> 9</html>

Complete boilerplate, ready to go. Your cursor lands in the body where you'll start adding content. This alone makes Emmet worth using, even if you never learn another abbreviation.

Practical Examples to Try

Here are some patterns you'll use constantly. Try typing each one and watching what expands:

form>input[type="text"]+input[type="email"]+button creates a simple form with two inputs and a submit button.

table>tr*3>td*4 generates a table with three rows and four columns in each row.

section.hero>h1.title+p.subtitle builds a hero section with a heading and subtitle, both already styled with classes.

The key is experimentation. Start with simple abbreviations, see what they produce, then gradually combine operators to build more complex structures.

Key Takeaways

Emmet isn't magic, and it's not required to write HTML. What it really means is this: once you understand HTML structure, Emmet removes the mechanical overhead of typing it out. You describe what you want in a compact syntax, and the editor handles the rest.

Start simple. Use Emmet for individual elements with classes. Then try creating pairs of siblings. Once that feels natural, add nesting. Before long, you'll find yourself thinking in Emmet abbreviations rather than raw HTML.

The best part? You don't have to memorize everything at once. Learn the basics child operator, sibling operator, multiplication, classes and you'll already be writing HTML faster. The advanced syntax can wait until you need it.

Open your editor, create an HTML file, and try the examples in this guide. The moment you see div.container>h1+p expand into proper HTML, you'll understand why developers who learn Emmet rarely go back to typing everything manually.

Share this post

You Might Also Like

Related posts based on tags, category, and projects

Master the fundamentals of CSS selectors to precisely target and style HTML elements, from basic element selectors to more specific class and ID targeting strategies.

A complete guide to HTML tags and elements, explaining the difference between the two, how they work together to structure web pages, and the most common patterns you'll use every day as a developer.

Ever wondered what happens after you hit Enter in your address bar? This guide breaks down how browsers transform URLs into interactive web pages, covering everything from networking to rendering.

Understanding the difference between TCP and UDP protocols, their real-world use cases, and how HTTP actually sits on top of TCP in the networking stack.