How a Browser Works: A Beginner-Friendly Guide to Browser Internals

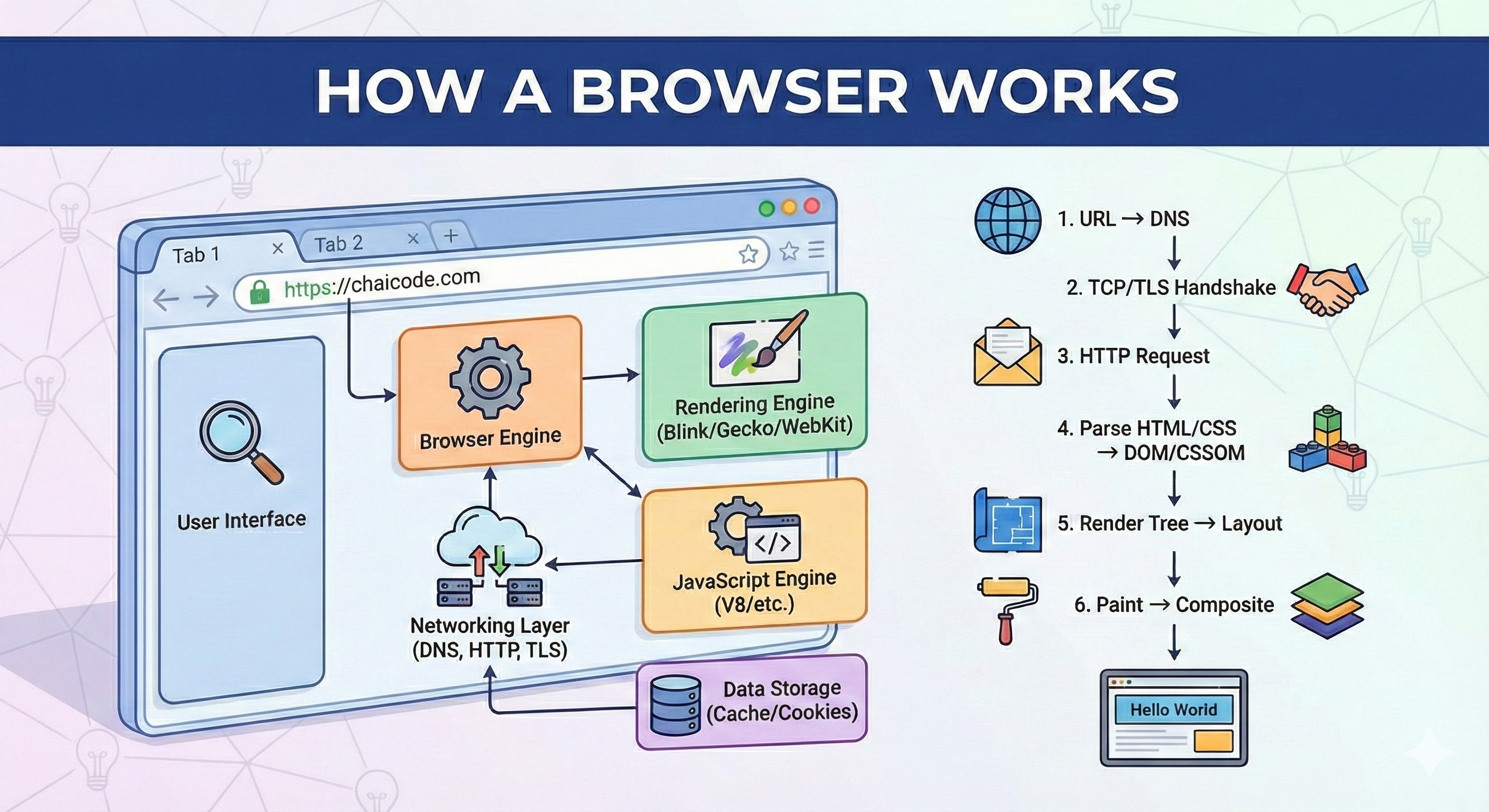

Ever wondered what happens after you hit Enter in your address bar? This guide breaks down how browsers transform URLs into interactive web pages, covering everything from networking to rendering.

You type a URL, press Enter, and boom a complete website appears on your screen. Seems instant, right? But here's the thing: your browser just orchestrated dozens of complex operations in milliseconds. Let's break down what actually happened.

What Is a Browser, Really?

Beyond the obvious "it opens websites" answer, a browser is basically an operating system for the web. Think about it Chrome, Firefox, and Safari don't just display pages. They manage networking, parse complex code, execute JavaScript at near-native speeds, render graphics, and keep everything secure through sandboxing. All simultaneously.

Modern browsers aren't simple applications anymore. They're sophisticated software architectures running multiple processes, each with specific jobs and security boundaries. Early browsers were monolithic everything ran in one process. One tab crashes, everything goes down. Worse, malicious scripts could access memory from other tabs. Modern browsers solved this with multi-process architecture, treating each tab as a separate process with restricted permissions. One tab crashes? You see a "sad tab" icon, but everything else keeps running.

The Main Parts of a Browser

Before we dive into the journey from URL to pixels, let's map out the browser's architecture. These components work together like an orchestra:

User Interface (UI): Everything you see except the actual webpage content. Your address bar, back/forward buttons, tabs, bookmarks menu that's all UI. It's your control panel for the browser.

Browser Engine: This acts as a bridge between the UI and the rendering engine. When you click the back button, the browser engine tells the rendering engine what to do. It's the coordinator.

Rendering Engine: The star of the show. This component parses HTML and CSS, then paints the parsed content onto your screen. Chrome uses Blink, Firefox uses Gecko, Safari uses WebKit. They all do the same job with slightly different approaches.

Networking Layer: Handles everything network-related DNS lookups, HTTP requests, TLS handshakes. It's your browser's connection to the internet.

JavaScript Engine: Executes your JavaScript code. V8 in Chrome, SpiderMonkey in Firefox, JavaScriptCore in Safari. These engines don't just interpret code anymore; they compile it to machine code for speed.

Data Storage: Manages cookies, localStorage, IndexedDB, and the browser cache. Your browser remembers things between visits here.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ User Interface (UI) │

│ [Address Bar] [Tabs] [Back/Forward] │

└─────────────────┬───────────────────────────┘

│

┌─────────────────▼───────────────────────────┐

│ Browser Engine │

│ (Coordinates everything) │

└─────┬──────────────────────────┬────────────┘

│ │

┌─────▼─────────┐ ┌──────────▼──────────┐

│ Rendering │ │ Networking │

│ Engine │ │ Layer │

│ (Blink/etc) │ │ (HTTP/DNS/TLS) │

└───────┬───────┘ └─────────────────────┘

│

┌───────▼────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ JavaScript │ │ Data Storage │

│ Engine │ │ (Cache/Cookies/etc) │

│ (V8) │ │ │

└────────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘

What Happens When You Type a URL and Press Enter?

Let's trace the complete journey. You type chaicode.com and hit Enter. Here's what your browser does:

Step 1: Networking - Fetching the Content

First, the browser needs to figure out where chaicode.com actually lives on the internet. Domain names are for humans; computers need IP addresses.

DNS Resolution: Your browser checks its cache first. Domain names get cached at multiple levels browser cache, OS cache, router, and finally your ISP's DNS resolver.

DNS works hierarchically. Your ISP's resolver asks a Root Server "Who handles .com?" The Root Server points to the .com TLD server. Then the resolver asks "Who handles chaicode.com?" The TLD server points to the authoritative name server, which finally returns the IP address: 172.67.213.172.

This multi-step lookup adds latency. That's why browsers do DNS prefetching they scan pages for links and resolve domain names in the background before you click.

TCP Connection: Now the browser establishes a TCP connection through a "three-way handshake." The browser sends SYN, server responds with SYN-ACK, browser sends ACK. This synchronizes sequence numbers for reliable data delivery. Each round trip adds 50-200ms of latency.

TLS Handshake: For HTTPS sites, there's an additional TLS handshake. Browser and server negotiate encryption algorithms. Server sends its certificate to prove identity. Browser verifies it against trusted Certificate Authorities. If valid, they generate session keys. This adds 2-3 round trips but ensures secure communication.

HTTP Request: Finally, the browser sends an HTTP GET request including headers like User-Agent and Accept. The server responds with a status code (200 OK if successful) and the HTML document.

Step 2: Parsing HTML and Building the DOM

The browser receives HTML, which is just text. But it needs a structured representation it can work with. Enter the DOM (Document Object Model).

What parsing means: Think of parsing like reading a sentence and understanding its grammar. When you read "The cat sat on the mat," you mentally break it down into subject, verb, and location. You're parsing English.

Here's a simple example with math: 3 + 4 * 2

Expression: 3 + 4 * 2

Parsing creates a tree:

+

/ \

3 *

/ \

4 2

This tree respects operator precedence.

The computer evaluates: 4 * 2 = 8, then 3 + 8 = 11

HTML parsing works similarly. The browser reads your HTML:

html1<html> 2 <body> 3 <h1>Hello World</h1> 4 <p>Welcome to my site</p> 5 </body> 6</html>

And creates a tree structure:

html

└── body

├── h1 ("Hello World")

└── p ("Welcome to my site")

This tree is the DOM. Every HTML tag becomes a "node" in the tree. The browser can now traverse, query, and modify this structure. This is what JavaScript manipulates when you call document.getElementById().

Why a tree? Trees represent hierarchical relationships perfectly. Your <h1> is a child of <body>, which is a child of <html>.

Here's the important part: HTML parsing is incremental. The browser doesn't wait for the entire document it starts building the DOM as bytes stream in from the network. This is why you sometimes see pages render progressively.

HTML is also fault-tolerant. Forget to close a tag? The browser figures it out. Nest tags incorrectly? The browser corrects it. This forgiveness is baked into the spec, but it adds complexity and processing time to the parser.

Step 3: Parsing CSS and Building the CSSOM

While the browser parses HTML, it also encounters CSS either in <style> tags, external stylesheets, or inline styles. CSS needs its own parsing process.

CSS gets parsed into the CSSOM (CSS Object Model), which is also a tree structure:

css1body { 2 font-size: 16px; 3} 4h1 { 5 color: blue; 6 font-size: 32px; 7} 8p { 9 margin: 10px; 10}

The CSSOM looks like:

body

├── font-size: 16px

├── h1

│ ├── color: blue

│ └── font-size: 32px

└── p

└── margin: 10px

Here's the key difference from DOM: CSS parsing is all-or-nothing. The browser can't start rendering until it has the complete CSSOM. Why? Because styles cascade and override each other. A style defined at the bottom of your CSS file might override one at the top. The browser needs to know all the rules before applying them.

This makes CSS "render-blocking." When the browser encounters a <link> tag pointing to an external stylesheet, it pauses rendering until that CSS file downloads and parses. This is why performance guides recommend inlining critical CSS the styles needed for above-the-fold content. By putting those styles directly in the HTML, you eliminate a network request that blocks rendering.

CSS selectors also have performance implications. Complex selectors like div.container > ul li:nth-child(3) a take longer to match than simple ones like .link. The browser reads selectors right-to-left, so it first finds all a tags, then filters for those that match the rest of the selector chain. Simpler selectors mean faster CSSOM construction.

Step 4: Combining DOM and CSSOM into the Render Tree

Now the browser has two trees: DOM (the structure) and CSSOM (the styles). It combines them into a Render Tree.

DOM + CSSOM = Render Tree

DOM: CSSOM: Render Tree:

html body {...} body (styled)

└── body h1 {...} ├── h1 (blue, 32px)

├── h1 p {...} └── p (10px margin)

└── p

The Render Tree only contains nodes that will actually be visible. Elements with display: none don't make it into the Render Tree because they won't be painted. This tree is purely about what needs to be rendered.

Step 5: Layout (Reflow) - Calculating Positions

The Render Tree knows what to display and how it should look, but it doesn't know where everything goes on the screen. That's the job of the Layout phase (also called Reflow).

The browser walks the Render Tree and calculates the exact position and size of each element. It computes geometry: "This <h1> is 300px wide and starts at position (20, 10)." This calculation starts at the root and flows down the tree.

This is computationally expensive. If you change an element's width or height, the browser has to recalculate layout for that element and potentially all its children and siblings. That's why animating width or height causes performance issues you're triggering layout on every frame (60 times per second).

There's a particularly nasty performance trap called "layout thrashing." This happens when you read a layout property (like offsetHeight) and then immediately write one (like setting width). The browser has to recalculate layout to give you the correct read value. Do this in a loop and you're triggering layout repeatedly. The solution? Batch all reads together, then batch all writes.

Step 6: Paint (Rasterization) - Creating Pixels

After layout, the browser knows where everything goes. Now it needs to actually draw pixels. The Paint phase converts each node into actual pixels on layers.

Think of painting like filling in a coloring book. You know where each shape is (layout), now you're adding colors, borders, shadows, and backgrounds.

The browser doesn't paint everything on one canvas. It creates multiple layers. Think of layers like transparent sheets stacked on top of each other. Elements with position: fixed, transform, opacity, will-change, or certain other properties often get their own layers.

Why layers? Performance and correctness. If an element with position: fixed stays in place while you scroll, the browser doesn't need to repaint the entire page. It can move the fixed element's layer independently. If an element animates with transform, the browser can update just that layer without repainting everything around it.

But layers aren't free. Each layer consumes memory. Creating too many layers (by overusing will-change or transform: translateZ(0) hacks) can actually hurt performance, especially on mobile devices with limited memory.

The paint process itself has costs. Some CSS properties are more expensive to paint than others. Box shadows require calculating and rendering blur effects. Gradients need interpolation across pixels. Text rendering with web fonts involves complex glyph rasterization. The browser has to do all this work before pixels appear on screen.

Step 7: Composite and Display

Finally, the browser composites all the layers together in the correct order and displays them on your screen. This is where the GPU helps out it's really good at blending layers together.

Here's the full flow:

URL Entered

↓

[DNS Resolution] → IP Address

↓

[TCP + TLS Handshake] → Secure Connection

↓

[HTTP Request] → HTML Response

↓

[HTML Parse] → DOM Tree

↓ ↓

[CSS Parse] → CSSOM Tree

↓ ↓

└──[Combine]──┘

↓

Render Tree

↓

[Layout/Reflow] → Calculate positions

↓

[Paint] → Create pixel layers

↓

[Composite] → Combine layers

↓

Display on screen

JavaScript Execution and the Main Thread

JavaScript runs on the main thread the same thread that handles parsing, layout, and paint. This is why long-running JavaScript blocks rendering. If your script takes 500ms to execute, the browser can't update the UI during that time. The page feels frozen.

When the browser encounters a <script> tag during HTML parsing, it stops. It has to download, parse, and execute the JavaScript before continuing. This is because JavaScript can modify the DOM or change styles. The browser can't safely continue parsing until it knows what the script will do.

This is why the async and defer attributes exist. Scripts with defer download in parallel but execute only after HTML parsing completes. Scripts with async download in parallel and execute as soon as they're ready. Modern best practice? Put scripts at the bottom of the body or use defer.

The JavaScript engine uses Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation. Your code gets parsed, initially interpreted for fast startup, then the engine profiles it to find frequently-run functions. These "hot" functions get compiled into native machine code for speed.

But here's the catch: JavaScript is single-threaded. Network requests, timers if these ran synchronously, your UI would freeze constantly. The solution? The Event Loop manages asynchronous operations without blocking. When you call fetch(), the browser handles the request in the background. When the response arrives, a callback gets queued. The Event Loop executes callbacks when the call stack is empty.

Promises use a special microtask queue with priority over regular tasks. This is why Promise callbacks run before setTimeout callbacks, even if the timeout is 0ms.

Browser Engine vs Rendering Engine

Quick clarification: these terms can be confusing.

Browser Engine: The coordinator. It sits between the UI and the rendering engine. When you click refresh, the browser engine handles that event and tells the rendering engine to reload the page.

Rendering Engine: The workhorse. It parses HTML/CSS, builds the DOM/CSSOM, creates the Render Tree, and handles layout and painting. This is Blink, Gecko, or WebKit.

Different terms, different jobs. The browser engine manages; the rendering engine renders.

Why This Matters for Developers

Understanding this pipeline helps you write better code. Here's how this knowledge translates to real performance wins:

Minimize Reflows: Reading layout properties like offsetHeight and then writing properties like width causes a forced reflow. Batch your DOM reads together, then batch your writes. Libraries like FastDOM automate this batching.

Animate Smart: Animating transform and opacity is smooth because these properties only trigger compositing, not layout or paint. The browser can move layers around on the GPU without recalculating anything. Animating left, top, width, or height triggers layout on every frame:

javascript1// BAD: Triggers layout + paint on every frame 2element.style.left = "100px"; 3 4// GOOD: Only triggers composite 5element.style.transform = "translateX(100px)";

Critical Rendering Path: The path from HTML to pixels is the Critical Rendering Path. Optimize it by inlining critical CSS, deferring non-critical JavaScript, and minimizing DOM depth. Every render-blocking resource delays initial paint.

Async Operations: Since JavaScript runs on the main thread (same thread for layout and paint), long-running scripts block rendering. Break long tasks into chunks using requestIdleCallback, move heavy computation to Web Workers, and use async/await for I/O instead of blocking.

Understand the Cost: Different operations have different costs. Changing color only triggers paint. Changing width triggers layout, then paint. Changing transform only triggers composite. Chrome DevTools Performance panel shows exactly which phase each operation triggers.

The browser is highly optimized, but it can't fix architectural problems. Poor DOM structure, inefficient selectors, or layout thrashing will be slow regardless of browser optimizations. Your job is to work with the browser's architecture, not against it.

Key Takeaways

The browser is a remarkably complex piece of software that makes the web work. When you type a URL and press Enter:

- The browser resolves the domain to an IP address through DNS

- It establishes a secure connection using TCP and TLS

- It fetches the HTML document via HTTP

- It parses HTML into a DOM tree and CSS into a CSSOM tree

- It combines both into a Render Tree containing only visible nodes

- It calculates exact positions and sizes during Layout

- It paints pixels onto layers

- It composites those layers and displays the result

Each step has performance implications. Understanding this flow turns you from someone who writes code that works into someone who writes code that works fast. The browser is your runtime knowing how it thinks makes you a better developer.

Share this post

Resources

- For curious people, here's my even more in-depth study on browser internals.

- How the web works

- Critical rendering path

- Prefetching, preloading, prebrowsing

- Parsing HTML documents

- Preload, Prefetch And Priorities in Chrome

- Layers and Compositing

- TCP 3-Way Handshake & Reliable Communication Explained

- How DNS Resolution Works: Understanding the Internet's Phonebook

- Gecko Reflow Visualization

You Might Also Like

Related posts based on tags, category, and projects

Master the fundamentals of CSS selectors to precisely target and style HTML elements, from basic element selectors to more specific class and ID targeting strategies.

Learn how Emmet transforms HTML writing from tedious typing into powerful abbreviations that expand into complete markup, saving time and reducing errors for beginners and professionals alike.

A complete guide to HTML tags and elements, explaining the difference between the two, how they work together to structure web pages, and the most common patterns you'll use every day as a developer.

Understanding the difference between TCP and UDP protocols, their real-world use cases, and how HTTP actually sits on top of TCP in the networking stack.