How the Internet Remembers Addresses: Understanding DNS Record Types

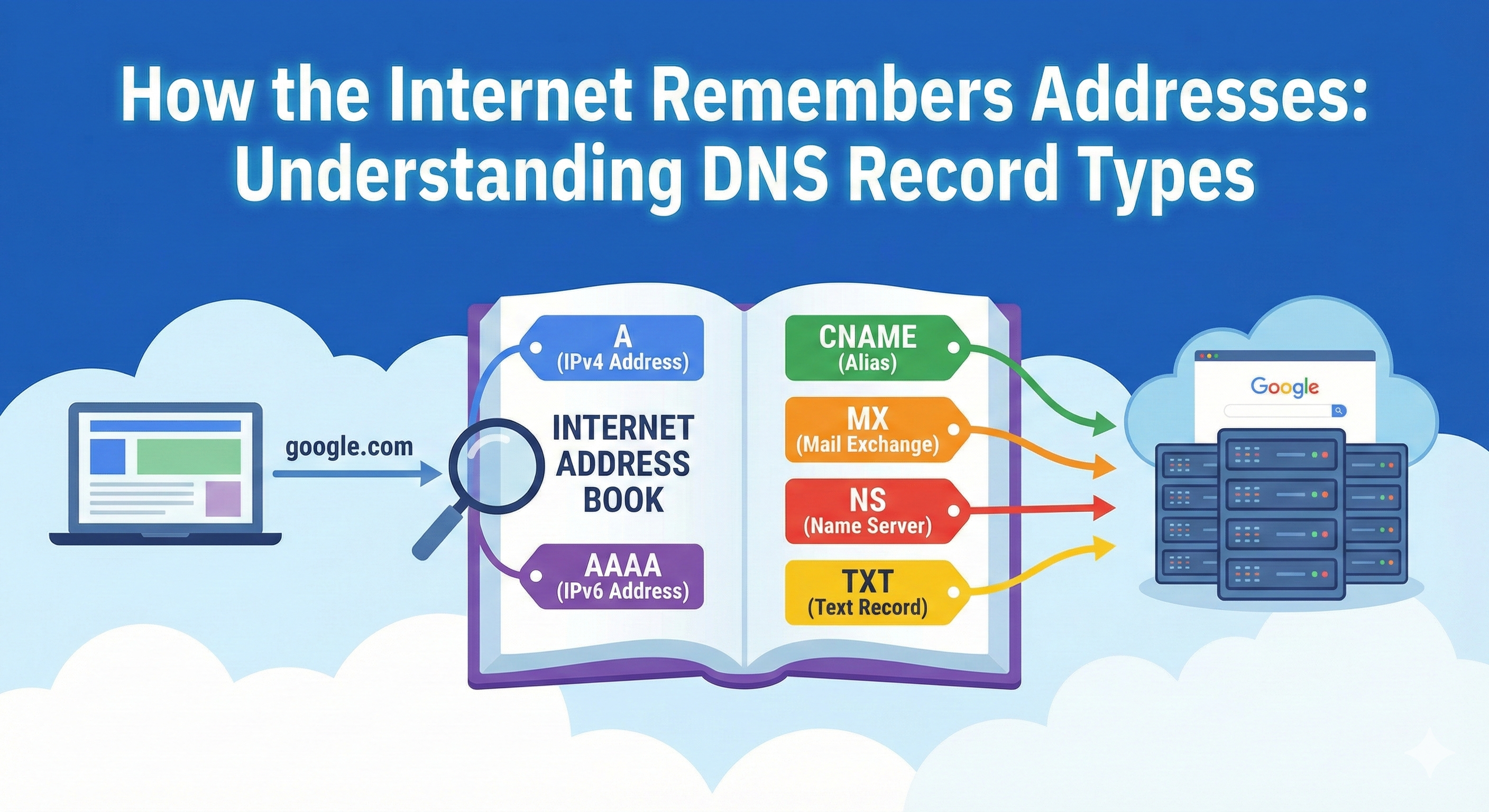

Ever wondered how your browser knows exactly where to find a website? Learn how DNS records work as the internet's address book, translating domain names into destinations. This beginner-friendly guide explains A, AAAA, CNAME, MX, NS, and TXT records without the jargon.

How does your browser know where a website lives?

When you type "google.com" into your browser, something interesting happens behind the scenes. Your computer doesn't actually know where Google's servers are located. It doesn't have a map, it doesn't have GPS coordinates, and it certainly doesn't have a phone number to call. Yet within milliseconds, you're staring at the Google homepage.

The answer is DNS, and it's one of those invisible systems that makes the internet actually work. Let's understand how.

What is DNS? (The Phone Book of the Internet)

DNS stands for Domain Name System, but the technical name doesn't really explain what it does. Think of it this way: DNS is like a massive phone book for the internet. Except instead of mapping names to phone numbers, it maps domain names (like "example.com") to IP addresses (like "192.0.2.1").

Here's the problem DNS solves: computers communicate using IP addresses, long strings of numbers like 142.250.185.46. Humans, on the other hand, remember names much better than numbers. DNS bridges this gap.

The Basic Flow

You type: example.com

↓

Browser asks DNS: "Where is example.com?"

↓

DNS responds: "It's at 93.184.216.34"

↓

Browser connects to: 93.184.216.34

↓

You see: The website

Without DNS, you'd have to memorize IP addresses for every website you visit. Imagine telling your friend, "Check out my blog at 185.199.108.153!" Not exactly catchy.

Why DNS Records Exist

DNS doesn't just store one piece of information per domain. A website needs much more than just an IP address to function properly. It needs to know:

- Where to send email

- Which servers are authoritative for this domain

- How to handle subdomains

- Where verification codes and security information live

- Whether to use the older IPv4 or newer IPv6 protocol

This is where DNS records come in. They're like different pages in that phone book, each containing a specific type of information about a domain. Let's explore the most important ones.

Understanding Name Servers: The NS Record

Before we dive into other record types, we need to understand who's actually in charge of a domain. That's where the NS record comes in.

What Problem Does It Solve?

The internet has millions of domains. No single server can store information about all of them. Instead, each domain has designated "name servers" that are responsible for holding all of its DNS records.

Think of NS records as saying: "If you want to know anything about example.com, go ask these specific servers. They're the authoritative source."

Real-World Example

example.com

Name Server: ns1.exampleserver.com

Name Server: ns2.exampleserver.com

When your browser wants to know about example.com, it first asks, "Who knows about this domain?" The internet responds, "Go ask ns1.exampleserver.com or ns2.exampleserver.com. They're the authorities."

Most domains have multiple name servers (primary and backup) for reliability. If one goes down, the others can still answer questions about the domain.

Finding the Server: The A Record

Now we get to the heart of DNS: the A record. This is the most fundamental DNS record type.

What Problem Does It Solve?

The A record answers one simple question: "What IPv4 address does this domain point to?"

The "A" stands for "address," and this record creates the direct connection between a domain name and where that website actually lives on the internet.

Real-World Example

example.com → 192.0.2.1

When you type "example.com" in your browser, the DNS lookup finds this A record and says, "Okay, connect to 192.0.2.1." Your browser then connects to that IP address and loads the website.

The House Address Analogy

Think of an A record like a house address. Someone asks, "Where does John live?" You say, "123 Main Street." The A record is exactly that: the DNS is saying, "example.com lives at 192.0.2.1."

Most websites have just one A record, but popular websites might have several, pointing to different servers. This helps distribute traffic across multiple servers (a technique called load balancing).

The Future of Addresses: The AAAA Record

The Internet is running out of IPv4 addresses. There are only about 4.3 billion possible IPv4 addresses, and we've nearly exhausted them. The solution? IPv6.

What Problem Does It Solve?

The AAAA record is exactly like an A record, but for IPv6 addresses instead of IPv4. IPv6 addresses are much longer but provide an almost unlimited number of possible addresses.

Real-World Example

example.com (IPv4) → 192.0.2.1

example.com (IPv6) → 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

Notice how much longer the IPv6 address is? That's the trade-off: longer addresses, but far more of them.

When Are AAAA Records Used?

Not every device or network supports IPv6 yet, so most websites have both A records (IPv4) and AAAA records (IPv6). When your device tries to load a website, it will use whichever protocol it supports. If it supports both, it usually prefers IPv6.

Name Pointing to Another Name: The CNAME Record

Here's where things get interesting. What if you want multiple domain names to point to the same place?

What Problem Does It Solve?

The CNAME record (Canonical Name) lets you create an alias. Instead of pointing a domain directly to an IP address, you point it to another domain name.

Real-World Example

Let's say you have:

example.com → 192.0.2.1 (A record)

www.example.com → example.com (CNAME)

blog.example.com → example.com (CNAME)

Now, when someone visits "www.example.com" or "blog.example.com," the DNS says, "Those are just nicknames for example.com. Let me look up example.com's A record for you."

The Contact Name Analogy

Think of CNAME like a contact in your phone. You might have "Mom," "Mother," and "Home" all pointing to the same phone number. You could store the number three times, but it's easier to have two nicknames pointing to the main contact. If Mom changes her number, you only update it once.

A vs CNAME: Common Confusion Cleared

Here's a confusion that trips up beginners:

- A record: Points directly to an IP address (192.0.2.1)

- CNAME record: Points to another domain name, not an IP

You cannot have both an A record and a CNAME record for the same name. It's one or the other. Also, CNAME records have a limitation: you can't use them for the root domain itself (example.com), only for subdomains (www.example.com, blog.example.com).

Delivering Email: The MX Record

Email doesn't work the same way as web traffic. When someone sends an email to you@example.com, how does it know where to deliver it?

What Problem Does It Solve?

The MX record (Mail Exchange) tells email servers where to deliver messages for a domain.

Real-World Example

example.com

MX Priority 10: mailhost1.example.com

MX Priority 20: mailhost2.example.com

When someone sends an email to you@example.com, the sending mail server asks DNS, "Where should I deliver mail for example.com?" The DNS responds with the MX records.

The Post Office Analogy

Think of MX records like postal service routing. When you mail a letter to a city, the postal service doesn't deliver it to just any building in that city. They have specific post office locations that handle mail for that area. Similarly, MX records tell the internet which mail servers handle email for a domain.

Priority Numbers

Notice the priority numbers (10, 20)? Lower numbers are tried first. If mailhost1 is down, the email server will try mailhost2. This provides backup in case the primary mail server isn't available.

NS vs MX: Common Confusion Cleared

Both records point to servers, but they serve different purposes:

- NS record: "Who is responsible for ALL DNS information about this domain?"

- MX record: "Where should EMAIL for this domain be delivered?"

Your name servers and mail servers are usually completely different machines.

Extra Information Storage: The TXT Record

The TXT record is the Swiss Army Knife of DNS. It can store arbitrary text information.

What Problem Does It Solve?

The TXT record was originally designed for human-readable notes, but today it's primarily used for verification and security purposes.

Real-World Examples

Domain Verification:

example.com

TXT: "google-site-verification=abc123xyz"

When you want to prove to Google that you own example.com, they give you a unique code to add as a TXT record. When Google's systems see that code in your DNS, they know you control the domain.

Email Security (SPF):

example.com

TXT: "v=spf1 include:_spf.google.com ~all"

This TXT record tells other email servers, "Only these servers are allowed to send email on behalf of example.com." It helps prevent spammers from forging emails that appear to come from your domain.

Email Authentication (DKIM):

example.com

TXT: "v=DKIM1; k=rsa; p=MIGfMA0GCSq..."

This stores a public key used to verify that emails claiming to come from your domain are actually legitimate.

The Bulletin Board Analogy

Think of TXT records as a bulletin board attached to your domain. You can post verification codes, security policies, or other important notices that various services need to read.

How DNS Records Work Together

Here's where the magic happens. A single website uses multiple DNS records working in harmony. Let's see a complete example:

Example: A Small Website Setup

Domain: mywebsite.com

NS Records (Who's in charge):

ns1.cloudprovider.com

ns2.cloudprovider.com

A Record (Where the website lives):

mywebsite.com → 203.0.113.50

AAAA Record (IPv6 version):

mywebsite.com → 2001:db8::1

CNAME Records (Aliases):

www.mywebsite.com → mywebsite.com

blog.mywebsite.com → mywebsite.com

MX Records (Email delivery):

Priority 10: mail.emailprovider.com

Priority 20: backup-mail.emailprovider.com

TXT Records (Verification and security):

"google-site-verification=unique-code-here"

"v=spf1 include:_spf.emailprovider.com ~all"

The Complete Journey

When someone visits www.mywebsite.com:

- Browser asks: "Where is www.mywebsite.com?"

- DNS checks NS records: "Ask ns1.cloudprovider.com"

- Name server checks CNAME: "www.mywebsite.com is an alias for mywebsite.com"

- Name server checks A record: "mywebsite.com is at 203.0.113.50"

- Browser connects: To IP address 203.0.113.50

- Website loads: Success!

When someone sends an email to contact@mywebsite.com:

- Email server asks: "Where should I deliver mail for mywebsite.com?"

- DNS checks MX records: "Try mail.emailprovider.com first"

- Email delivers: To the mail server

- Inbox receives: The email

Meanwhile, TXT records sit quietly in the background, ready to verify your ownership when Google asks, or to tell email servers which servers are legitimate.

Common Scenarios Explained

Scenario 1: Moving Your Website

When you move your website to a new hosting provider with a new IP address, you only need to update the A record:

Old: mywebsite.com → 203.0.113.50

New: mywebsite.com → 198.51.100.75

Because www.mywebsite.com uses a CNAME pointing to mywebsite.com, it automatically follows the change. One update fixes everything.

Scenario 2: Using Third-Party Email

Many people host their website with one provider but use Google Workspace or Microsoft 365 for email. The setup looks like this:

A Record (website):

mywebsite.com → hosting-provider-ip

MX Records (email):

Priority 10: google-mail-server.com

Different records, different services, working together seamlessly.

Scenario 3: CDN Integration

When you use a Content Delivery Network (CDN) like Cloudflare, you might change:

Before: mywebsite.com → your-server-ip (A record)

After: mywebsite.com → cdn.cloudflare.com (CNAME)

Now, traffic routes through Cloudflare's network before reaching your server.

Key Takeaways

DNS records work as a team to make your domain functional:

- NS records designate who's in charge of your domain's DNS information

- A records connect your domain name to an IPv4 address

- AAAA records do the same for IPv6 addresses

- CNAME records create aliases pointing to other domain names

- MX records route email to the right mail servers

- TXT records store verification codes and security policies

Each record solves a specific problem, and together they create the complete identity of your domain on the internet. The next time you type a website address or send an email, you'll know there's an intricate but elegant system working behind the scenes to make it all happen.

DNS is truly the unsung hero of the internet, quietly translating human-friendly names into computer-friendly addresses billions of times every day. And now you understand how it all works.

Also, a big thanks to Cloudflare for the docs.

Share this post

You Might Also Like

Related posts based on tags, category, and projects

A practical guide to understanding DNS resolution using the dig command, exploring how domain names are translated to IP addresses through root servers, TLD servers, and authoritative nameservers.

Understanding the difference between TCP and UDP protocols, their real-world use cases, and how HTTP actually sits on top of TCP in the networking stack.

Master the fundamentals of CSS selectors to precisely target and style HTML elements, from basic element selectors to more specific class and ID targeting strategies.

Learn how Emmet transforms HTML writing from tedious typing into powerful abbreviations that expand into complete markup, saving time and reducing errors for beginners and professionals alike.